May the thought be comforting

that true happiness is not always the enjoyment of life,

but arises from sorrow.”

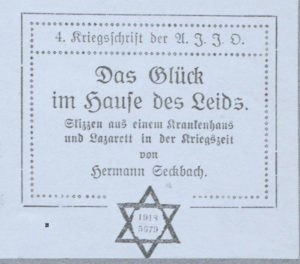

Hermann Seckbach (1918)

The diverse life stories out of Gumpertz´ infirmary (1888-1941), a Jewish nursing home for frail and terminally ill needy people in Frankfurt´s East End, would fill a comprehensive book. On behalf of all people involved, this article introduces the foundresses Betty Gumpertz and Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, the founding physician Dr. med. Alfred Günzburg, the administrator and author Hermann Seckbach, the last president Dr. jur. Richard Merzbach, as well as “Gustchen” and Siegmund Keller, two dedicated residents. A separate article is devoted to the matron Rahel (Spiero) Seckbach.

Foundresses and Eponyms: Betty Gumpertz and Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild

It is known that the maiden name of Betty Gumpertz, the foundress and eponym of Gumpertz´ infirmary which existed from 1888 until 1941, was Cahn: In the former Jewish quarter (Frankfurt´s Jewish ghetto, 1462 – 1796) “there were several families named Cahn which were not related to each other. The oldest and most influential family named Cahn can be proven by [sic] their ancestral houses , especially by the house Pforte, where the family had lived since 1515. In this corner house as well as in the houses separated therefrom and the attached houses “Wedel”, “Green Door”, “Golden Pincer” and “Red Door” the descendants had been living for three centuries” (quoted by MJ Ffm, “Families” section). Betty Cahn married into the Gumpertz family, which immigrated from Emmerich to Frankfurt am Main in 1649 and took the name Gumpertz (also Gumpert, Gumperz): “Several of its members were in a close business relationship to the large royal courts of Prussia and Hanover, whereby the family acquired tremendous wealth. The family had lived in Frankfurt for several centuries and got involved among other things also with the welfare of the Jewish community” (quoted by ibid., also see Kasper-Holtkotte 2010). Betty Gumpertz continued the tradition and dedicated her dependent foundation, the association Gumpertz´ Infirmary, to two deceased relatives: her husband Leopold Gumpertz and their son Heinrich (Gump statute 1895, page 5). The association being in charge of the infirmary received, in addition to many small donations and voluntary activities, larger endowments from the two Frankfurt Jewish communities (cp. Gumpertz´ infirmary 1909: 10-23), for example, from Betty Gumpertz´ former peers Träutchen (Thekla) Höchberg and Raphael Ettlinger and from the siblings Hedwig Hausmann and Dr. med. Franz Hausmann.

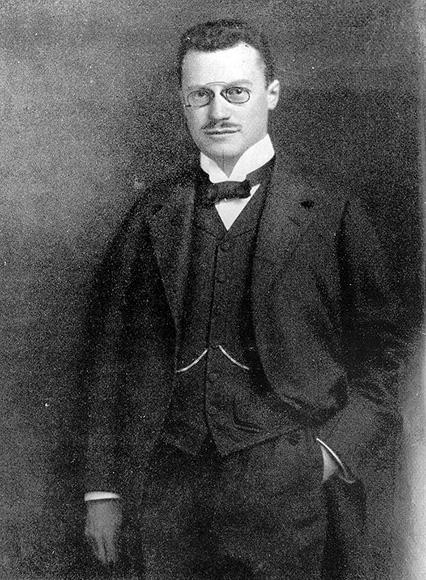

Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute (Paul Arnsberg Collection)

In 1905, a financially strong patron appeared with the banker and founder family von Goldschmidt-Rothschild: To the memory of Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1857 – 1903), who died at the age of only 45, her mother Mathilde von Rothschild and the widower Max von Goldschmidt-Rothschild established an independent foundation, which was later supported by Minka´s five children Albert, Rudolf, Lili, Lucy and Erich as well as by their sister Adelheid de Rothschild, who lived in Paris. Minka (originally Minna Caroline, cp. Lenger 1994; also see Rothschild 1994) was the youngest of three daughters of Mathilde and Wilhelm Carl, who was Frankfurt´s last Rothschild banker and died in 1901. As a committed foundress – among other things she founded the still existing Rothschild´s Residential Home for Ladies for deprived female tenants – Minka possibly supported the Gumpertz´ care project in her lifetime. In 1907, the Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Foundation, which was affiliated to the association Gumpertz´ Infirmary, erected a big modern building (“front house”) at 62-64 Röderbergweg which was why the home was also called “Rothschild´s infirmary”; along with another, smaller, later restored villa (“rear building”) it formed Gumpertz´ infirmary. In 1938, the Nazi rulers expelled the long-established family von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (cp. Heuberger (Hg.) 1994a and 1994b; Kasper-Holtkotte 2010; Liedtke 2006: 109 et seq.; also see Ferguson 2002) to Switzerland. Prior to that they lost all their Frankfurt estates (ISG Ffm: Collection History of People Page 2: Sign. S2/12.001). After the end of the NS-regime one of Minka´s granddaughters, Nadine von Mauthner, returned to her native city, where she concealed her origins for a long time (ibid., Sign. 18.335). Her father and Minka´s eldest son, the banker and diplomat Albert von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, committed suicide in 1941 and was buried in the exile grave of the Goldschmidt-Rothschild family in Lausanne (also cp. Lessing Grammar School 1998).

Dr. med. Alfred Günzburg: foundation physician and promoter of Jewish health car

He worked in a most unselfish and most sacrificial way for our home. The rapid blossoming of the home is due to his work. He made a special contribution to the sanitary and practical design of the magnificent building (“front house” of the infirmary, B.S.) of the Minka-von-Goldschmidt-Rothschild Foundation, which was erected under his insightful direction (Gumpertz´ infirmary 1909: 5).

That was how the association board of Gumpertz´ infirmary appreciated its leaving foundation physician, the internal medicine specialist Dr. med. Alfred Günzburg, who was born in Offenbach am Main on March 27, 1861. “Günzburg´s Reaction” (also “Günzburg-Reagent”, “Günzberg-Sample”) is named after him, which is a diagnostic procedure he developed for the detection of elevated levels of stomach acid. As of January 1, 1909 Dr. Günzberg gave up his job at the infirmary and switched to the internal medicine department of Frankfurt´s Jewish Community Hospital (on Königswarterstrasse) before leaving to the newly opened hospital of the Jewish community (on Gagernstrasse) in 1914, where he had been involved in the planning. He had already been working in the Königswart hospital for years where he had trained the first two Jewish nurses in Germany, Rosalie Jüttner from Poznan and Minna Hirsch from Halberstadt. He was very much interested in the professionalization and establishment of nursing as a Jewish female profession. Thus, he was the co-initiator of the association for Jewish nurses that was founded in Frankfurt am Main in 1893 and the co-organizer of the first assembly of delegates of German-Jewish training associations for nursing in 1904. At the end of 1935 the national socialists expelled the over 70-year-old Alfred Günzburg from Germany. He settled down in what was then Palestine, where his son, Dr. med. Ludwig Günzburg (born in Frankfurt am Main in 1895), previously a practitioner in Frankfurt and involved with the association of socialist physicians, had already fled in 1933. In 1945, Alfred Günzburg died at the age of 84 in Ramoth Hashavim near Tel Aviv, where his son managed a home of the Cupath Cholim for chronically ill people (cp. Günzburg 1946 [obituary]; Toren 2005). Ludwig Günzburg, who set up the first rehabilitation clinic in Israel, died in 1977 (cp. Drexler [et al.] 1990: 35).

In 1910, the practitioner Dr. med. Jakob Meyer became Alfred Günzburg´s successor as the senior physician of Gumpertz´ infirmary (cp. Kallmorgen 1936: 354 as well as Gumpertz´ infirmary 1913 et seqq.). At the time when Dr. Meyer was serving as a medical officer of the reserve, his representative Dr. med. Gustav Löffler (cp. Kallmorgen 1936: 341) temporarily managed the infirmary along with the military hospital (cp. Gumpertz´ infirmary 1913 et seqq.). Known by name are also the following physicians (ibid 1909: 5): the practical dentist Heinrich Borchard (cp. Kallmorgen 1936: 229), the pediatrician Dr. Max Plaut (ibid: 373), the surgeon Dr. Otto Rothschild (ibid: 390) and the ophthalmologist Dr. Michael Sachs (ibid: 393). The practitioner Dr. Hermann Schlesinger (ibid: 400) and the otologist Dr. Heinrich Seligmann (ibid: 411) also belonged to the older generation (1850’s) of physicians of the infirmary.

© Jüdisches Museum Frankfurt am Main

The last president: Dr. jur. Richard Merzbach

Following Ferdinand Gamburg, Charles L. Hallgarten and Julius Goldschmidt, the lawyer and notary Dr. jur. Richard Merzbach became the last president of the association Gumpertz´ Infirmary. He was born in Frankfurt am Main on October 26, 1873 (cp. Dölemeyer/Ladwig-Winters 2004: 174). In accordance with information which still needs to be verified (cp. http://www.geni.com/people/Richard-Joseph-Merzbach/6000000000158338859, all links in the article called on October 24, 2017) he was the son of Marie née Heim from Fürth and Emanuel Merzbach from Offenbach am Main and married to Trude (Gertrude) née Alexander from Königsberg in Prussia. Occasionally, Dr. Merzbach officiated as (liberal) president of the Jewish municipal council. He was particularly interested in the Jewish nursing institutions: In 1911, he was a member of the board of the Jewish health insurance for women and from (at least) 1917 of Gumpertz´ infirmary.

The files available from the Frankfurt am Main institute of urban history (e.g. ISG Ffm: magistrate records Sign. 8.957) document how uncompromisingly the lawyer defended the existence of the infirmary after the seizure of power by the Nazis in 1933. He could, however, not prevent the forced forced dissolution of the nursing home around 1939 and the transfer of its residents to Gumpertz´ last domicile at 15 Danziger Platz. Already in 1935, the NS-authorities had withdrawn notarial powers from Richard Merzbach. On December 1, 1938 he was banned from his profession as a lawyer and deleted from the directory of solicitors. In October 1938 the Merzbach couple fled to the USA.

Dr. Richard Merzbach died in Seatlle on August 22, 1945 followed by his wife Trude obviously only a few days later on August 25, 1945. Their daughters had fled from Nazi Germany already in 1933: Edith Alice Lobe worked in US-exile as a social worker (cp. obituary of Dave Birkland: http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19930130&slug=1682755), Hilde Birnbaum (cp. obituary of Mary Spicuzza: http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20030817&slug=birnbaumobit17m ) studied economic sciences and was married to Zygmunt William Birnbaum, a professor of mathematics. They were committed to a sophisticated social and health system and made their mark as civil-rights activists for social justice and women´s emancipation. Richard Merzbach would have surely been proud of the fighting spirit of his daughters.

The soul of the home: Hermann Seckbach, administrator and author

From 1904 until 1939 Hermann Seckbach was the administrator of Gumpertz´ infirmary. This employment was both profession and vocation for him at the same time. Reliable biographical data are difficult to determine, since Hermann Seckbach comes from a family which spread from Heddernheim (today a district of Frankfurt) and Frankfurt am Main to Halberstadt (Saxony-Anhalt) (cp. Klamroth 2006). The given male names “Lassar” (also Elzar, Lazar, Lazarus) and “Hermann” were common in his family. Maybe he was related to the architect Max Seckbach. During World War I Hermann Seckbach additionally managed the military hospital that had been set up inside Gumpertz´ infirmary. At the beginning of 1919 he married the matron Rahel Spiero, their daughter Ruth Rosalie was born in the same year. On the occasion of Hermann Seckbach´s 25th service anniversary, the newsletter of the Jewish community of Frankfurt am Main reported (magazine 4, December 1929: 154): “Along with his self-sacrificing, caring activities Mr Seckbach has made a special contribution to the founding institution’s synagogue which had been built only with support from foundations. Its artistic individuality causes a solemn mood to the residents and visitors.” In 1939, Hermann Seckbach was expelled from his position in life to English exile by national socialists.

The author Hermann Seckbach also dedicated his publications on Jewish and social topics (cp. Seckbach 1917, 1918a, 1918b, 1928, 1933), especially in economic times of need, to the public relations work of Gumpertz´ infirmary. In 1917 he informed “Frankfurt´s News” [Frankfurter Nachrichten] about the (official) 25th anniversary of the nursing home (1917). In 1918, he campaigned for better “Social Care for emotionally disturbed Jewish People with a Nervous Disorder!” in the magazine “In the German Empire” of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith (1918b). A brief review published in the newsletter of the Jewish community of Frankfurt am Main (June 1928, magazine 10) made the following statement about his book “Sabbath Spirit. Stories and Sketches”: “The book has come from the intuitive world of traditional Judaism and can, although it does not raise any literary claims, be recommended all the more as reading for young people because the net profit is passed on to Gumpertz´ infirmary.” Hermann Seckbach did the same with his income from the following book “The Seder at Grüneburg Castle. Tales from the children´s corner” (1933). His probably most impressive publication is the writing “Happiness in the House of Sorrow. Sketches of a Clinic and Military Hospital in Wartime” published in 1918. He dedicated it to “His beloved brother Lassar Seckbach, Halberstadt” (1918a). In narrative miniatures Hermann Seckback erected a monument to the residents like the blind and paralyzed rabbi daughter Rosa Dobris (18-21).

Committed Residents: “Gustchen” and Siegmund Keller

Hermann Seckbach´s glimpse into the complex and very special inner world into a (in this case Jewish) home for chronically frail and incurably ill people reveals at the same time its advanced care concept: instead of incapacitating custody, the promotion of greatest possible independence. Each biography had its place in Gumpertz´ infirmary, and residents and nursing staff could learn from each other. One of his loving portraits Seckbach dedicated to a girl called “Gustchen” (probably “Auguste”, the family name has not been passed down) who was visually impaired due to a head tumor: “Surrounded by 60 other fellow sufferers she, the blind one, was a ray of hope. […] Up before six o´clock in order to bring the heavily suffering residents a hot morning draft quickly. Then going from room to room, singing a funny song in order to show everyone a service of love. […] No matter how much the nurses were working, Gustchen, the happy Gustchen, always had to be with them when it came to bedding the sick or to assisting a paralyzed person here and to bringing cooling to a feverish sufferer there” (Seckbach 1918a: 60).

Further information is obtained from a newspaper article written by the visitor Fanny Cohn-Neßler: “In the women´s division I recognized a 17-year old girl who had the size of a six-year old and the mind of a three-year old child. A big baby face, only bulging lips. Thick braid with a pink ribbon loop; a thick chubby hand was laughingly stretched out to me. She was happily eating her soup at the children´s table. The girl is from Moravia. Would be a “sight”. A handsome two-year old boy in a snow-white bed; his head pressed into the pillow with eyes closed. The nurse picks him up – the other half of his face is completely crooked. He cannot move. The child has no sensation, it takes food, that is all. […] I leave the much too sad cases unmentioned” (Cohn-Neßler 1920, page 174 et seq.)

The patients usually were of Jewish faith and all age groups. Most of them had never been able to learn a profession or to start a family. Among them were social pensioners and homeless people having been transferred by Frankfurt´s welfare office to Gumpertz´ infirmary. Senility, early dementia and strokes made great demands on nursing and medicine along with incurable ulcers, bone diseases and arthritis, multiple sclerosis and poliomyelitis causing permanent restrictions of movement ability. Often these patients were unwilling bed-wetters and have bowel control problems. They were among the “poorest of the poor” (quoted in advertisement in: The Israelite, No. 24, June 16, 1921, page 12). Many were from Frankfurt and the Hessian surrounding countryside, some were also from today´s Rhineland-Palatinate. The 20-year old Minna Kann (born in Lonndorf near Giessen in 1873) was admitted after her parents´ death. Leopoldine Karbe (born in Lich / Upper Hesse in 1851), admitted in 1908, died in the infirmary on December 14, 1922. The 70-year old Salomon Kahn (born in Steinfischbach / Taunus in 1849), a tradesman by profession, was also transferred to the infirmary by the welfare office of his hometown in 1919.

For reasons of cost Gumpertz´ infirmary had been increasingly serving as a nursing home since 1922. So died: “[…] the retired teacher Mr Gerson Mannheimer at the age of 64. Due to a treacherous suffering he had been accommodated in Gumpertz´ infirmary for four years […]. During his career he worked as a teacher in various municipalities such as Zwingenberg, Babenhausen and Rüsselsheim. […] About 20 years earlier he already needed to give up his profession. So he fought the fight now […]” (obituary in: The Israelite, March 14, 1929).

Also due to the NS-era Salomon Goldschmidt, the former board member of the Jewish municipality Hochstadt (Hanau district), died in the infirmary, too: “The deceased, who had relocated to Frankfurt two years ago, was a Yehudi [Jew, B.S.] of deep piety, who devotedly participated in many shiurim [religious instructions, B.S.] […]. The rabbis Wolpert and Korn as well as Hermann Seckbach additionally described his special attachment to “his” Kehillah [community, B.S.] Gumpertz […]” (obituary in: The Israelite, February 17, 1938).

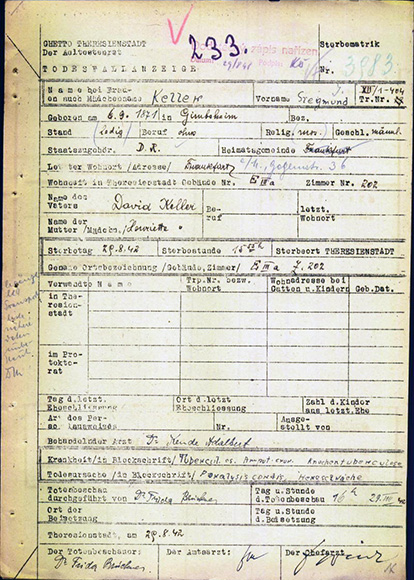

What Hermann Seckbach described as the nursing concerns of Gumpertz´ infirmary was also true for the resident Siegmund Keller: “And the ill and sick patients, who were accommodated here, they soon did not longer feel their suffering, they became new humans, who played their part in solving the problems of life” (Seckbach 1918a: 9). He was born in the Rhine Hessian wine town Gimbsheim (cp. Jewish history: Alemannia Judaica: http://www.alemannia-judaica.de/gibsheim_synagoge.htm; Alicke 2008 vol. 1: 1472 et seq.) as the son of Henriette and David Keller on September 6, 1871. Due to his chronic disease Siegmund Keller remained single and did not have a profession. In 1898, Gumpertz´ infirmary became his home – for more than four decades! He particularly attended to its intellectual and cultural centerpiece, the home synagogue (cp. Gumpertz´ infirmary 1936: 14). He possibly assisted in the organization of the Sabbath and the Jewish ceremonies in the rooms of the bed-ridden residents.

Siegmund Keller could have also died in Gumpertz´ infirmary, but he was forcibly transferred to Frankfurt´s last Jewish hospital (on Gagernstrasse) when all residents of the home at 15 Danziger Platz were evicted by the Nazis on April 7, 1941. The eviction was a torture for the residents, and many of them died in hospital. On August 18, 1942 Siegmund Keller was deported to Theresienstadt together with other patients as well as the matron of Gumpertz´ infirmary, Rahel Seckbach, and other nursing staff. The weakened patient survived the transport as if by a miracle, but succumbed to the inhumane camp conditions after a few days on August 29, 1942. According to his obituary Siegmund Keller suffered from tuberculosis and bone tuberculosis. As the official cause of death “paralysis of the heart” was given (cp. Theresienstadt Initiative, data base).

The author thanks Mr Lenarz (deputy director of the Jewish Museum of Frankfurt am Main) for quickly sending two Richard-Merzbach-photographs and giving permission for their reproduction, Mr Simonson (Leo Baeck Institute) for the reproduction permission of the Minka-von-Goldschmidt photograph as well as Prof. Stascheit (head of the Frankfurt am Main University of Applied Sciences publisher) for important information regarding Alred and Ludwig Günzburg.

Birgit Seemann, 2013, updated 2018

(Translated by Yvonne Ford)

Unbpublished sources

ISG Ffm: Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main:

Hausstandsbücher Gagernstraße 36: Sign. 686 (Teil 1); Sign. 687 (Teil 2)

Nullkartei

Personenstandsunterlagen

Sammlung Personengeschichte S 2: Sign. 398: Goldschmidt, Julius

Sammlung Personengeschichte S 2: Sign. S2/12.001: Goldschmidt-Rothschild, Familie

Sammlung Personengeschichte S 2: Sign. 18.355: Mauthner, Nadine von

Stiftungsabteilung: Sign. 157: Verein Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus

Stiftungsabteilung: Sign. 146: Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung (1939-1940)

Wohlfahrtsamt: Sign. 877 (1893–1928): Magistrat, Waisen- und Armen-Amt Frankfurt a.M.

Toren, Benjamin [Günzburg, Heiner] (2005): Die Familie Günzburg (Toren) von Frankfurt am Main. Unveröff. Ms. Privatarchiv Prof. Dr. Ulrich Stascheit, Frankfurt a.M.

Selected literature

Alicke, Klaus-Dieter 2008: Lexikon der jüdischen Gemeinden im deutschen Sprachraum. Gütersloh, 3 Bände.

Arnsberg, Paul 1983: Die Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden seit der Französischen Revolution. Darmstadt, 3 Bände.

Cohn-Neßler, Fanny 1920: Das Frankfurter Siechenhaus. Die Minka-von-Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung. In: Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums 1920, H. 16 (16.04.1920), S. 174-175. Digitale Ausg.: http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/judaica/.

Dölemeyer, Barbara/ Ladwig-Winters, Simone 2004: Kurzbiographien der Anwälte jüdischer Herkunft im Oberlandesgerichtsbezirk Frankfurt. In: 125 Jahre. Rechtsanwaltskammer Frankfurt am Main. Oberlandesgericht Frankfurt am Main. Rechtspflege. Ausstellung: Anwalt ohne Recht. Festveranstaltung 1.10.2004 Paulskirche Frankfurt am Main. Hg.: Rechtsanwaltskammer Frankfurt am Main, Oberlandesgericht Frankfurt am Main, S. 137-201

Dörken, Edith 2008: Hannah-Luise, Luise, Adele Hannah, Hannah Mathilde, Adelheid, Minna Caroline von Rothschild. Stifterinnen der Rothschildfamilie. „Gegen die Not und Bedrängnis der Mitmenschen“. In: dies.: Berühmte Frankfurter Frauen. Frankfurt/M., S. 78-89.

Drexler, Siegmund [u.a.] 1990: Ärztliches Schicksal unter der Verfolgung 1933–1945 in Frankfurt am Main und Offenbach. Eine Denkschrift. Erstellt im Auftr. der Landesärztekammer Hessen. 2. Aufl. Frankfurt/M.

Ferguson, Niall 2002: Die Geschichte der Rothschilds. Propheten des Geldes. Band II: 1848 – 1999. Stuttgart, München.

Günzburg, Alfred [Nachruf] (1946): M. R.: Alfred Günzburg. In: Aufbau 12 (1946) 2 (11.01.1946), S. 24, Spalte a, http://archive.org/stream/aufbau1219461946germ#page/n29/mode/1up.

GumpSiechenhaus 1909: Sechzehnter Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ in Frankfurt a.M. für das Jahr 1908. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky.

GumpSiechenhaus 1913ff.: Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ und der „Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung“. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky, 1913ff. Online-Ausg.:Frankfurt am Main : Univ.-Bibliothek, 2011: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-306391.

GumpSiechenhaus 1936: Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus. [Bericht von der Generalversammlung des Vereins.] In: Der Israelit, 20.05.1936, Nr. 21, S. 14f.: http://edocs.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/volltexte/2008/38052/original/Israelit_1936_21.pdf.

GumpStatut 1895: Revidirtes Statut für den Verein Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus zu Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.: Druck v. Benno Schmidt, Stiftstraße 22. [ISG Ffm: Sammlung S3/N 5.150].

Heuberger, Georg (Hg.) 1994a: Die Rothschilds. Bd. 1: Eine europäische Familie. Sigmaringen.

Heuberger, Georg (Hg.) 1994b: Die Rothschilds. Bd. 2: Beiträge zur Geschichte einer europäischen Familie. Sigmaringen.

Kallmorgen, Wilhelm 1936: Siebenhundert Jahre Heilkunde in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.

Kasper-Holtkotte, Cilli 2010: Die jüdische Gemeinde von Frankfurt/Main in der Frühen Neuzeit. Familien, Netzwerke und Konflikte eines jüdischen Zentrums. Berlin, New York.

Kingreen, Monica (Hg.) 1999: Zuflucht in Frankfurt. Zuzug hessischer Landjuden und städtische antijüdische Politik. In: dies. (Hg.): „Nach der Kristallnacht“. Jüdisches Leben und antijüdische Politik in Frankfurt am Main 1938 – 1945 Frankfurt/M., New York., S. 119-155.

Kirchheim, Simon [u.a.] 1904: Delegierten-Versammlung der Vereinigungen zur Ausbildung jüdischer Krankenpflegerinnen in Deutschland. Am 4. September 1904 zu Frankfurt a. M. im Schwesternheim Königswarterstraße 20. Frankfurt/M.

Klamroth, Sabine 2006: Die Mayers – die Halberstadts – die Bachs – die Seckbachs. In: dies.: „Erst wenn der Mond bei Seckbachs steht“. Juden im alten Halberstadt. Halle, S. 122-133 [siehe auch: http://www.juden-im-alten-halberstadt.de].

Lenger, Christine 1994: Der Name lebt weiter. Die Familie Goldschmidt-Rothschild. In: Heuberger (Hg.) 1994a: 190f. [mit Abb. v. Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild].

Liedtke, Rainer 2006: N M Rothschild & Sons. Kommunikationswege im europäischen Bankwesen im 19. Jahrhundert. Köln [u.a.].

Lessing Gymnasium 1998: Die jüdischen Schüler und Lehrer am Lessing Gymnasium 1897-1938. Dokumentation zur Ausstellung der Archiv-AG des Lessing Gymnasiums Frankfurt am Main Februar 1998. Frankfurt/M.

Rothschild, Miriam 1994: Die stillen Teilhaber der ersten europäischen Gemeinschaft. Gedanken über die Familie Rothschild II: Die Frauen. In: Heuberger (Hg.) 1994b, S. 159-170 [S. 166: Abb. von Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild mit ihrer Großmutter Mathilde von Rothschild].

Schiebler, Gerhard 1994: Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger. In: Lustiger, Arno (Hg.) 1994: Jüdische Stiftungen in Frankfurt am Main. Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger dargest. v. Gerhard Schiebler. Mit Beitr. v. Hans Achinger [u.a.]. Hg. i.A. der M.-J.-Kirchheim’schen Stiftung in Frankfurt am Main. 2. unveränd. Aufl. Sigmaringen 1994, S. 11-288.

Seckbach, Hermann 1917: Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Siechenhaus. Von Verwalter H. Seckbach. In: Frankfurter Nachrichten, 20.09.1917.

Seckbach, Hermann 1918a: Das Glück im Hause des Leids. Skizzen aus einem Krankenhaus und Lazarett in der Kriegszeit. Frankfurt/M. = Kriegsschrift der Agudas Jisroel Jugendorganisation; 4.

Seckbach, Hermann 1918b: Soziale Fürsorge für jüdische Nerven- und Gemütskranke! In: Im deutschen Reich. Zeitschrift des Centralvereins Deutscher Staatsbürger Jüdischen Glaubens, H. 10 (Okt. 1918), S. 403 (online: Univ.bibl. Frankfurt a.M.: Compact Memory: http://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm/periodical/pageview/2354746).

Seckbach, Hermann 1928: „Sabbatgeist“. Erzählungen und Skizzen. Frankfurt/M.: Sänger u. Friedberg.

Seckbach, Hermann 1933: Der Seder auf Schloß Grüneburg. Erzählungen aus der Kinderecke. Frankfurt/M.: Verlag des Israelit und Hermon.

Seemann, Birgit 2014: „Glück im Hause des Leids“. Jüdische Pflegegeschichte am Beispiel des Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses (1888-1941) in Frankfurt/Main. In: Geschichte der Pflege. Das Journal für historische Forschung der Pflege- und Gesundheitsberufe 3 (2014) 2, S. 38-50

Selection of internet sources [24.10.2017]