Jewish nursing history and genealogy using the example of the nurse Johanna Sämann

Whose purpose and work was it?

His, who sent out the generations from the start.

I, the Lord, the first, and with the last, I am he.”

Isaiah, 41, 4

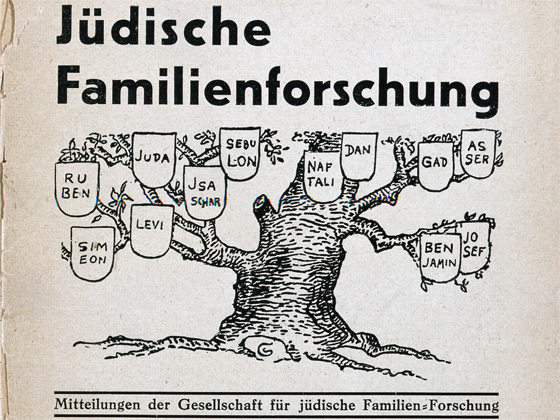

© Jewish Museum, Berlin, Photo: Jens Ziehe

The foundations for the choice of a profession – sometimes even a vocation – is often laid in the parental home where first social learning processes generally take place.

Skills, deficits, the manner of dealing with demands and conflicts are in part passed on from generation to generation. For the socio-historical reappraisal of nursing, apart from the biographical research (cf. “Biographisches Lexikon zur Pflegegeschichte ”; Grypma 2008; Hanses/Richter 2009), historical family research (genealogy) is of the utmost importance. Research opportunities also open up especially for the Jewish part of German nursing history: Where did the Jewish nurses came from? How did they grow up? How did they live their Jewish identity? Which factors influenced their decision to enter the nursing profession? But also: What happened with the nurses´ families during the NS period? The investigations and reconstruction of Jewish nursing biographies face different challenges than that of Christian ones.

Grandchild of a Torah scholar: the nurse Johanna Sämann

The results of previous investigations into the history of nurses in German-Jewish hospitals reveal a relative homogeneity with regard to their social origin. In order to show some aspects clearly, a very well-researched family biography of the nurse Johanna Sämann is presented in the following.

On 25th February 1891 she was born as Johanna [Johanne] Levi in the village Altengronau (today´s district von Sinntal near Schlüchtern, Main-Kinzig-region) and maternally influenced by the Württembergian, paternally by the Hessian country Judaism. Both parents came from respected families: The mother, Mirjam (Mari) Levi née Sulzbacher, was a daughter of the rabbi David Sulzbacher from (Bad) Mergentheim, “who used to be well known as a famous scholar in the local area” (Israelite, volume 28, magazine no. 52 (07-JUL-1887), page [943]-944, Beil). Hirsch Sulzbacher, Johanna Sämann´s uncle, taught as a teacher in the south Hessian town Groß-Bieberau. When Mirjam Levi died short before her 80th birthday in 1930, the obituary stated: “With Mrs Levi we lost one of those wonderful Jewish female characters who have, unfortunately, become increasingly rare these days” (Israelite, volume 71, magazine no. 49 (4-DEC-1930), page 9). Johanna Sämann´s father, Raphael Levi, worked as a Torah scroll writer (Sofer), shohet (shochet) and administrator of the cemetery of the Hessian-Jewish community Altengronau for many years. He died in 1926 over 70 years of age and was also commemorated by the “Israelite”: “Descending from a famous family of scholars – even the grandfather of the deceased had done the divine work of writing Torah scrolls here – he was also a rare godly man and an artist in his field, to which eloquent witness is bore by the Torah scrolls written and tefelin produced by him” (Israelit, volume 67, magazine 24 (10-JUN-1926), page 7).

Apparently the Sulzbachers and Levis set a particular example of Jewish religiousness and learning, social justice (Zedakah) and charity (Gemilut Chassadim) to their environment. Having been established in her Jewish identity by her family biography already, Johanna Sämann met almost perfectly the criteria for the professional profile based on the nursing training designed by Dr. Gustav Feldmann and other protagonists (Feldmann 1901): between Jewish integration efforts and an often anti-Semitic environment, the Jewish nurse should – in addition to her professional and dedicated service at Jewish and non-Jewish patient beds – vouch for the positive values of Judaism.

Family biography and nursing profession

Johanna Sämann’s background is, also in other respects exemplary for the family biography of Jewish nurses. Many were drawn from country regions (cf. to country Judaism Richarz/Rürup 1997) to Jewish hospitals (Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Hamburg, Köln, Breslau et al.) for training reasons. Jewish family research is often combined with regional research, especially when “Jewish villages” (Jeggle 1999) with a high Jewish percentage of the population are concerned. The main difference of socialization experience between Christian and Jewish nurses was that the age-long existence of Jews as a vilified and always vulnerable minority with simultaneous anti-Jewish outbursts, pogroms and expulsions was embedded in family memory. Occupational bans had the effect that the Jewish nursing staff did not consist of farmers´, artisans´ or workers´ children, but almost solely of members of the social class of small merchants, cattle dealers, shopkeepers or, like Johanna Sämann, Torah scholars or village teachers. However, their economic situation was precarious: especially from the last third of the 19th century the Jewish communities declined rapidly, as young Jewish men sought their livelihood in the cities or emigrated to America. Like other country rabbis, Johanna Sämann´s grandfather David Sulzbacher had to close his Jeschiva (Talmud school for young Jewish men) and to support his family with commercial activities. Her father Raphael Levi, who was in charge of the small Jewish community of Altengronau, had to feed his wife and eight daughters of which Johanna was the second youngest. She needed to find a husband as breadwinner or to learn a profession – and chose nursing (like her sister Sara Levi). The chances of marriage for religious Jewish women had declined further, not only because of the emigration of young fellow believers, but also due to the increased number of marriages with Christian women in the course of the integration (assimilation). Later Johanna Sämann married Sigmund Sämann, a widower, who was many years older than she and a Jewish Nürnberg merchant..At the age of 33 years Johanna gave birth to her only son Gerhard (Skyte/Skyte 2006).

Her decision to enter the nursing profession also corresponded to contemporary attributions, seemingly natural feminine qualities such as “motherhood, caring, tenderness”, virtues of “sacrifice, hard work, patience” (Walter 1991, page 9), which did not allow profitable employment opportunities for women in the German Wilhelmine Empire in the first place. However, these gender stereotypes concerned nurses of all denominations. The question concerning both Jewish and Christian nurses of whether the familial sibling status influenced / influences careers in the nursing profession, remains speculative: Did Julie Glaser become matron at Frankfurt´s Jewish hospital, since she as the eldest of four sisters had developed leadership potential and, additionally, came from a distinguished middle-class family, whereas Johanna Sämann, of whom such a promotion to a leadership position is not known, as the second youngest of eight sisters, was more likely one of the supervised younger siblings? Did Erika Neugarten as a member of the ironing personnel, on the other hand, not do any nurse training at Frankfurt´s Jewish hospital, since she, unlike Julie Glaser and Johanna Sämann, could not prove to live a so-called well-ordered family life?

Review: Travel into the family past after the Shoah

Johanna Sämann, her husband and her minor son were among the exterminated people of the Shoah. Survivors and descendants often go on an arduous and painful search for murdered relatives and family branches. However, genealogical research can also release energy, when traces of the lives and merits of missing persons are discovered and appreciated. Both perspectives are combined by the life account of Thea Levinsohn-Wolf (1907 – 2005), one of the few published personal accounts of German-Jewish nurses. In the book she dedicated an emotional Kaddisch (Jewish prayer for deceased) to her parents, her sister, the little nephew and more than 50 other relatives in total, who were victims of the Shoah. She found solace in the memory of her ancestors, whose traces in the Rhineland she followed on a trip through Germany in 1991: “Das Oberland” as my parents called the Hunsrück (a region in Rhineland-Palatinate) was almost daily mentioned at my parental home. That was their home, where their birthplaces were, as it says a song, and also their fathers´, grandfathers´ and great grandfathers´ […]. (Levinsohn-Wolf 1996, page 150). Advanced in years, Thea Levinsohn-Wolf had “an emotional time when experiencing the scenery and visiting the places, whose names have been familiar to me since my childhood. I have come full circle.” (ebd. S. 157).

Birgit Seemann, 2011 (updated 2020)

(Translated by Yvonne Ford)