For the care of the patients, for the edification of the parish, for the good of the city of our fathers”

The opening of Frankfurt´s Jewish Ghetto (1462 – 1796) and the granting of the long sought-for status as citizens (“isaelitische Bürger”) on 1st September 1824 (Heuberger/Krohn 1988, page 37) created the framework for the resolution of the cramped and outdated hospital system of the Ghetto time. Finally Frankfurt´s two Jewish communities – the Jewish community with a liberal majority and the smaller conservative Jewish religious community – could then establish a modern medical and care system. Both Jewish-religious (with their own synagogues and kosher cooking) and inter-denominational oriented hospitals and nursing homes emerged; even the conservative-Jewish institutions admitted non-Jews in accordance with the Bikkur-Cholim-provisions.

As early as 1829, a few decades prior to the establishment of equality of Frankfurt´s Jewish population on 8th October, 1864, the “Hospital of the Jewish Health Insurances ” opened its doors at Rechneigrabenstrasse 28 – 20 (next to the “Neuer Börneplatz” memorial). The Rothschild banker family had the double building erected: “The barons Amschel, Salomon, Nathan, Carl, Jacob von Rothschild put up this house in accordance with the wishes of their immortalized father [Mayer Amschel Rothschild, d.V.); “for the care of the patients, for the edification of the parish, for the good of the city of our fathers”; a monument of filial reverence and fraternal unity” (quotation by Arnsberg 1983, book volume 2, page 123). The hospital emerged from the two Jewish insurance companies for men (established in 1738 and 1758) and the Jewish health insurance for women (established in 1761) of Frankfurt´s Jewish Ghetto. All three health insurance companies were social benefit societies with their own wards where in-patients and out-patients received treatment. In 1826 Siegmund Geisenheimer, authorized representative of the banking house Rothschild M.A. and a member of the hospital administration, managed the centralization of the health insurances under the same roof in an organizational tour de force. In 1831 the hospital had up to 30 beds (Jewish health insurance for men: about 15 beds; Jewish health insurance for women: about 12 beds); an old Frankfurt City Guide (no author [1843], page 48) also praised its “little synagogue” (“Kippe-Stubb”). Claire Simon (“Sister Claire”) became matron of the health insurance for women in 1917. By September 1942 the hospital of the Jewish health insurance companies came to a sad end as a collection site prior to the Frankfurt deportations; allied air attacks on Nazi Frankfurt destroyed the twin building of the health insurance for men and the health insurance for women (cp. Unna 1965; Schiebler 1994, page 163-141).

The Dr. Christ Children´s Hospital (1845 – 1943/44) on Theobaldstrasse (today Theobald-Christ-Strasse), in Frankfurt affectionately called “Spitälchen” , was the common project of two closely befriended physicians and founders: the Gentile Dr. Theobald Christ and the baptized Jew Dr. Salomo Friedrich (Salomon) Stiebel, both Protestants. 30 years later, the Jewish benefactress Louise von Rothschild from Frankfurt established the “Clementine Girls´Hospital” on Bornheimer Landwehr 10 which was named after her daughter Clementine. The emergence of today´s Clementine Children´s Hospital on Theobald-Christ-Strasse 16 resulted from these two respected institutions of Frankfurt´s patient care that admitted girls and boys irrespective of religion and social origin (cp. Hövels et al. 1995; Reschke 2011).

In 1870 the “Hospital of Georgine Sara von Rothschild Foundation” was founded – first as the “Foreigner’s Hospital” with six beds – at Unterweg 20. Initially, the hospital, also known as “Rothschild´s Hospital”, took care of needy Jewish patients, especially those who did not find accommodation in other Jewish treatment centers. It was called “Georgine Sara von Rothschild”, named after the daughter of the founding couple Hannah Mathilde and Wilhelm Carl von Rothschild; she was also the cousin of Clementine von Rothschild who had likewise died early and for whom the Clementine Children´s Hospital had been named. The body responsible for the “Rothschild´s Hospital” was the neo-orthodox Jewish religious community (IRG ): established in 1850; it positioned itself as guardian of Jewish tradition over against the larger liberal Frankfurt Jewish community from which it also institutionally broke away in 1876 (cp. Heuberger/Krohn 1988, page 74-77). In 1878 a new building, financed by Mathilde and Wilhelm von Rothschild, was opened, initially with 40 beds at Röderbergweg 97, followed by buildings at Röderbergweg 93 and Rhönstrasse 50 (staff residence). The senior doctor Dr. Marcus (Markus) Hirsch participated in these developments from the beginning. Seven decades later, in April 1941, the National Socialists also closed this hospital and sent both staff and patients to Frankfurt’s last remaining Jewish hospital (Gagernstrasse 36, see below). Around 1943 air attacks on Frankfurt destroyed the building and property of “Rothschild´s Hospital”. The chronicler of Jewish history, Dr. Paul Arnsberg, a qualified attorney, achieved the re-establishment of the Georgine Sara von Rothschild Foundation in 1976 (cp. Lustiger 1994; Krohn 2000).

“Jewish communities were – even in times of great hardship – exemplary in building and maintaining a number of social welfare institutions (e.g. hospitals, orphanages, infirmaries, retirement homes, soup kitchens etc.). The basis for this is the obligation in Judaism to provide assistance to the poor and the sick and to assure the strengthening and restoration of the material independence of each needy person” (Werner, Klaus et al.: Jews in Heddernheim. In: Heuberger 1990, page 46). This was also true for the once independent Jewish communities of outlying districts which are now incorporated into the city of Frankfurt am Main. Despite the fact that few historical sources are available, some information about Jewish nursing in Bergen-Enkheim, Bockenheim, Fechenheim, Griesheim, Heddernheim, Höchst, Niederursel or Rödelheim have become discovered in the meantime (cp. Arnsberg 1983, book volume 2, page 507-595; Heuberger 1990). From 1874 the small Jewish endowed hospital of the “Foundation of Joseph and Hannchen May for sick and needy people” existed in Rödelheim at Alexanderstrasse 96 (seat of the foundation), not far from today´s Josef-May-Strasse. Due to the incorporation of Rödelheim into Frankfurt on 1st April 1910, the hospital (until 1937 with Jewish prayer room) became part of the municipal hospital and was later used as a retirement home. Today (as of 2017) it houses the Social and Rehabilitation Center West, still a retirement and nursing home, albeit non-Jewish.

Further research is needed on the institutional history of the private hospitals which also offered inpatient treatment established by Jews in Frankfurt am Main. The first doctor´s office of this kind was probably the private hospital of Dr. Siegmund Theodor Stein which was opened in 1867 and later expanded to include the treatment of internal and nervous disorders. On 1st April 1904 the Frankfurt neurologist Prof. Dr. Adolf Albrecht Friedländer , of Jewish origin and born in Vienna, established the “Hohe Mark” hospital, a large hospital for psychiatry, psychotherapy and psychosomatic medicine set in the heart of the Taunus region (close to Oberursel near Frankfurt), as a private clinic for the European high nobility (cp. http://www.hohemark.de/startseite/, all following links searched dated 24-Oct-2017). The “Herxheim Clinic and Polyclinic for Skin and Venereal Diseases“ became well-known in Frankfurt; Paul Arnsberg (1983 book volume 2, page 271; book volume 3, page 187, page 277) gave various locations for the institution: Friedberger Landstrasse 57, Heiligkreuzgasse and Holzgraben (both without house numbers) as well as Zeppelinallee 47 (Herxheim villa). In 1876 Dr. Salomon Herxheimer , who along with his younger brother and successor Prof. Dr. Karl Herxheimer was recognised as being among the German pioneers of dermatology, founded the respected clinic which also helped uninsured needy persons suffering from skin diseases. In memory of her deceased husband, Fanny Herxheimer established the “Medical Councillor Dr. Salomon Herxheimer Foundation” in 1899 to provide continuing care to poor patients suffering from skin disorders. Her sister Rose Livingston (Löwenstein), who had been baptized a Christian in 1891, founded the still active “Nellini Church Foundation” with initially 25 places for single elderly women of Evangelical faith at Cronstettenstrasse 57 (cp. http://www.nellinistift.de/). A street name in Frankfurt´s Gallus neighbour recalls the merits of the Herxheimer family (Arnsberg 1983; Lachenmann 1995; also cp. Kallmorgen 1936).

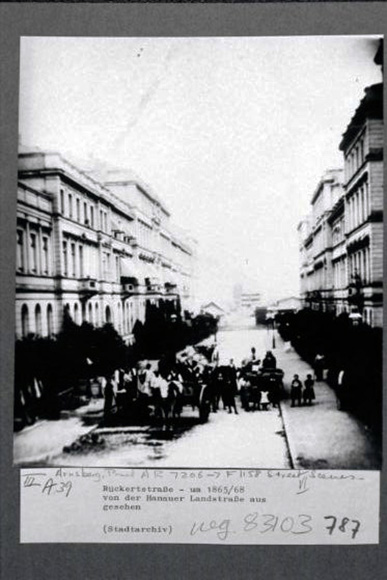

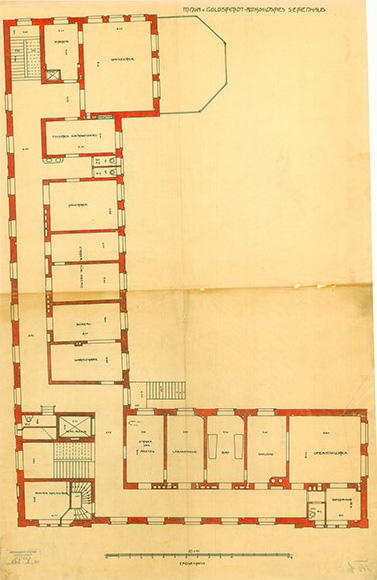

The „Gumpertz‘ infirmary“ (1888-1941) founded by Betty Gumpertz at Röderbergweg 62 – 64 was an ambitious Jewish women´s project within the circle of the conservative Jewish religious community. It supported the poorest of the poor in Frankfurt´s east end whose numbers continued to increase due to the migration of refuges who were victims of anti-Semitic pogroms in East Europe. Nursing homes for patients with contagious and, at that time, incurable diseases were referred to as infirmaries up to the 18th century. The Gumpertz´ infirmary specialized in the care of socially disadvantaged individuals suffering from chronic diseases. Opened in 1888 on Rückertstrasse, it soon moved into a new building with 20 places at Ostendstrasse 75 in 1892 and into a new building with 60 beds at Röderbergweg 62 – 64 in 1907. Among the foundresses, in addition to Betty Gumpertz and Träutchen (Thekla) Höchberg, were the sisters Minna Caroline (Minka) von Goldschmidt-Rothschild and Adelheid de Rothschild, which was why the Gumpertz´ infirmary was sometimes also referred to as “Rothschild´s infirmary”. Thekla Mandel, as matron from the beginning until her marriage, was an active participant in affairs; she was followed by Rahel (Spiero) Seckbach in 1907. In 1938 the main building of “Gumpertz´ Infirmary” was sold under NS-conditions through the City of Frankfurt to the “Hospital of the Holy Spirit” (Schiebler 1994, page 135); at last (1941) it stayed at Danziger Platz 15. Since 1956, the “August-Stunz-Center ” (Röderbergweg 82), a retirement home of the Worker´s Welfare (cp. to Gumpertz´ infirmary Lenarz 2003; Otto 1998; Schiebler 1994, page 135, page 282; also cp. Müller 2006, page 97), has existed on its former premises.

© Dr. Edgar Bönisch, 2009

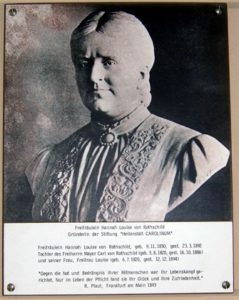

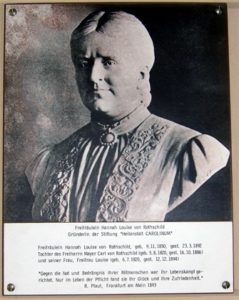

On 16th October 1890 Hannah Louise von Rothschild founded the medical facility and dental hospital Carolinum at Bürgerstrasse 7 (today known as Wilhelm-Leuschner-Strasse, a different Bürgerstrasse continues to exist in Frankfurt today); it was a state-of-the-art hospital also serving people in need. The Carolinum, named after her deceased father Mayer Carl von Rothschild, developed into a central and still respected institution of dentistry in Frankfurt. Hannah Louise von Rothschild was actively supported by the non-Jewish senior doctor Dr. Dr. Jakob de Bary – chairman of the Carolinum foundation board until his death in 1915 – and his daughter, Luise de Bary, who was matron for many years. In 1910 the Carolinum moved into Ludwig-Rehn-Strasse and affiliated itself from the beginning with Frankfurt University which was founded through endowments on 26th October 1914. Due to the deft dealings of the non-Jewish board headed by Jakob de Bary´s son Dr. Dr. August de Bary , the Carolinum survived the Nazi era as the only Jewish foundation in Frankfurt. In 1978 the dental clinic moved into a new building on the clinic premises at Theodor-Stern-Kai 7 where it is still successfully and, in accordance with the wishes of the foundress Hannah Louise von Rothschild, also socially active as the Carolinum University Dental Institute of of Goethe University Frankfurt/Main (cp. http://www.med.uni-frankfurt.de/carolinum/).

With the Mathilde von Rothschild´s Children´s Hospital (1886 – 1941) at Röderbergweg 109, also known as Rothschild´s Children´s Hospital, Mathilde von Rothschild founded an institution, which offered needy Jewish (and on request also certainly non-Jewish) children free care and nutrition. Initially 12 children received free in-patient treatment, later up to 100 per year, and in 1932, the number had increased up to140. Further research in needed on the conservative-religious institution and its certainly mostly Jewish nursing staff. In June 1941 the National Socialists closed the children’s hospital. They admitted the remaining little patients together with the nursing staff to Frankfurt’s now last Jewish hospital (Gagernstrasse 36, see below), which was misused as collection site prior to deportation.

In 1904 the Jewish business couple Auguste and Fritz Gans (in 1895 baptized as Protestants) established an inter-denominational clinic called “Böttgerheim” at Böttgerstrasse 20-22 (cp. Gans/Groening 2006). A nursery and a state-recognized nursing school for the training of baby nurses were affiliated with this modern and socially progressive institution; the nurses´ house was located on the adjoining Hallgartenstrasse from 1909. In 1920 the City of Frankfurt am Main took over the Böttgerheim which was in financial need after the war, and passed it into the sponsorship of the newly founded city health department two years later. From 1921 – 1929 the well-known German-Jewish pediatrician Prof. Dr. Paul Grosser directed the children’s hospital. Under the NS-regime the Böttgerheim was called “Municipal Children´s Hospital” from 1934. The hospital and residential care facility was re-opened in 1947 and continued until the closure by the City of Frankfurt in 1975. Today (as of 2017) the old foundation building as well as an additional new building house a birthing and counseling center for the parents of babies and infants (www.geburtshausfrankfurt.de) – in accordance with the wishes of the donor couple Gans.

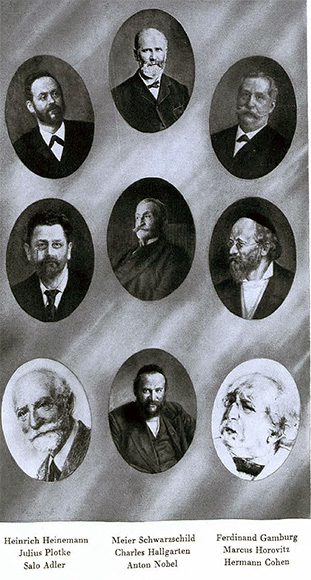

Due to generous donations from Frankfurt´s Jewish residents, the big “Hospital of the Jewish Frankfurt am Main Community”, which was built at Gagernstrasse 36 in 1914, became operational with initially 200 beds (cp. Hanauer 1914). The clinic with modern technologies, often called simply referred to the “Jewish hospital” (though many non-Jewish patients also sought and found treatment there), existed until the Nazi forced eviction in 1942. Its precursors were the “Old Jewish Hospital for Foreigners” (1796-1875) as well as the “Hospital of the Jewish Frankfurt am Main Community” on Königswarterstrasse (Königswarter Hospital, 1875-1914), both established in Frankfurt’s Jewish Ghetto. Senior doctor of the old Jewish Foreigners´ Hospital on Völckerschen Biergarten from 1817 was Dr. Salomo Friedrich (Salomon) Stiebel , later co-founder of the above-mentioned Dr. Christ´s Children´s Hospital . When Dr. Stiebel retired after working 40 years, the practitioner and gynecologist Dr. Heinrich Schwarzschild (1803-1878) advanced to be the second doctor in charge of the hospital. Not least due to his insistence could the founding of Königswarter Hospital at Grünen Weg 26 (later Königswarterstrasse) with 80 beds be realised in 1875; generous donors were the banker Isaac Löw Königswarter and his wife Elisabeth. Their ward for internal medicine was directed by the surgeon and obstetrician Dr. Simon Kirchheim from 1877; he was also an active promoter of professional Jewish nursing as a paid female profession. Rosalie Jüttner was probably the first Jewish student nurse at the Königswarter Hospital in Germany followed by Minna Hirsch, first matron of the Königswarter Hospital (closed in 1914) and the succeeding Jewish hospital on Gagernstrasse as well as of the “Association for Jewish Nurses of Frankfurt am Main”. Today a Christian-influenced institution is located on Königswarter Strasse (16 instead of 26), the Red Cross Hospital. (as of 2017).

Along with the new Jewish hospital, the nurses´ residence of the “Association for Jewish Nurses of Frankfurt am Main” was also opened in 1914. The internationally known diabetes researcher Prof. Dr. Simon Isaac was medical director and senior consultant of the ward for internal medicine until he was forced to emigrate in 1939, followed by Dr. Alfred Valentin Marx. Further senior medical consultants were: for the polyclinics, the medical councilor Dr. Adolf Deutsch , for the women´s hospital, Dr. Arnold Baerwald , for the Ear-Nose-Throat-Clinic, Dr. Max Meier , for the eye clinic, Dr. Isaak Horowitz and for the surgery department, Dr. Emil Altschüler, who was director from 1935 of the Bikur Cholim Hospital in Jerusalem (still operating in 2017). In April 1939, the City of Frankfurt am Main “purchased” the entire property of the hospital for RM 90,000 through so-called “Jews Contracts” in order to rent it back to the Jewish community afterwards (cp. in summary Karpf 2003). Upon arrival of staff and patients of the already closed Rothschild´s hospitals on Röderbergweg, a Gestapo report of 1942 listed almost 400 patients, more than 100 employees (including the medical and nursing staff) and 37 student nurses (Steppe 1997, page 246). In October 1942 the big Jewish hospital was also forcibly evacuated; the previously accommodated patients were deported to Theresienstadt and other death camps. From November 1942 there was only one Jewish ward in a “community accommodation” (collection and transit camp prior to deportation) at Hermesweg 5-7. Its closure in the night of the fourth to the fifth day of October meant the end of institutional Jewish nursing in Frankfurt am Main. After the war the senior citizen center of the Jewish community of Frankfurt am Main came into existence on the premises at Gagernstrasse 36. Until the present day, no Jewish hospital has been re-established in Frankfurt am Main (cp. to situation of the Jewish hospital systems after the Nazi era Arnsberg 1970).

Birgit Seemann, 2010, updated 2020

(Translated by Yvonne Ford)