1893 to 1940

Background for the founding of the association

XVI. Annual report of the Association of Jewish nurses in Frankfurt am Main 1909, Frankfurt am Main 1909, Title page

The profession of nursing developed in the second half of the 19th century in extra-familial nursing care. Important factors / conditions for this development were the professionalisation of medicine and the increasing number of hospitals which were opened. For the Jewish community of Frankfurt this was revealed in the establishment of the Hospital of the Israeli Community (Hospitals der Israelitischen Gemeinde), also known as the “Koenigswarter Hospital.” It provided places for 80 sick persons and was open for all members of the community and their employees. At a time when the necessity for professional nursing was still being discussed, only July 1, 1881 the presumably first nurse trained in a Jewish hospital was employed: Rosalie Jüttner.

The founding of the association and its goals

The doctors Simon Kirchheim and Alfred Guenzburg, and especially the banker Meier Schwarschild, planned the founding of an Association for the Promotion of Nursing. In addition, the trained nurses Minna Hirsch, Frieda Brüll, Klara Gordon, Lisette Hess and Thekla Mandel began to organize the Association of Jewish Nurses between 1889 and 1893. Both organizations were joined on October 23, 1893 under the name of the Association for Jewish Nurses of Frankfurt on Main („Verein für jüdische Krankenpflegerinnen zu Frankfurt am Main„). Minna Hirsch had already been elected as the matron of the Association. The head of the board of directors, made up of nine men, was Dr. Simon Kirchheim. The goals of the association were to train Jewish girls to be nurses and, in addition, to offer free care for the poor of all denominations. One of the financial supports of the association was to be paid private nursing care. Everyone who paid a membership fee became a member.

The first 10 years

The nursing students and the nurses were given accommodation in a rented apartment, referred to as the “little house” located just next to the hospital. After a few years they relocated to a house at Unteren Atzemer 16. In 1902 a new nurses’ residence was built on property next to the Israeli Hospital on Koenigswarter Street. A total of 43 nursing students were accepted for training in the first 10 years of the association’s existence. In that not all students who began their training completed it and not all remained in the association, there were 24 active nurses at the end of the 10 years. Thirteen of these nurses were involved in direct nursing care, one of them in care for the poor. Five of the nurses of the association worked in the Frankfurt hospital and three in Hamburg. Thekla Mandel had become matron of the Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses (Gumpertz‘s Asylum for the Sick), another nurse was on leave at this time. Six nurses were awarded the golden brooch for continuous service in the association. After the first 10 years Jewish nursing in Frankfurt had been firmly established. The need for further trained nurses remained great.

Developments at the beginning of the 20th century

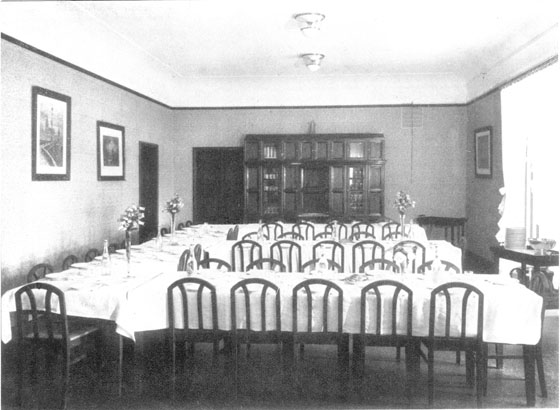

In the following years the influence of women in the association increased; a nurses‘ council was formed. The reputation of the training course for nursing was more highly valued after it became possible to sit for state-recognized nursing exams. The training was extended to one and a half years and more attention was given to continuing education for nurses. Through cooperative activities or being deployed in service nurses were also active in other locations such as Hannover and Basel. New areas of work were developed such as the milk kitchen for infants in the mother house. In 1914, in the meantime there were 40 active nurses; the hospital was moved into a larger and more modern building located at Gagernstrasse 36. Next to the hospital was a new nurses’ residence (Schwesternhaus) located at Bornheimer Landwehr 85. This house provided space for 60 nursing students and nurses as well as domestic staff in single and double rooms. There were common rooms, activity rooms and offices. The night watch had its own sleeping cubicle and nurses who were caring for patients with contagious diseases had a separate apartment.

First world war and the Weimarer Republic

During First World War the nursing association showed its patriotism: all nurses were at the disposal of the war medical service. The nurses‘ residence was converted into a military hospital, 850 soldiers were treated there throughout the war. A crash programm and brief nursing training were establishes, former nurses reported back for duty. Nurses were developed during war in different hospitals, i.e. the Jewish hospital, the Gumpertz’s asylum for the sick or the Israelite hospitals in Hanover and Strasbourg. Some served near the front or in a German Red Cross hospital train.

Due to societal changes during and after the war, private nursing lost in significance. Nursing was provided primarily at the Israeli Community Hospital, in the milk kitchen which provided infant care and in the children’s home run by the Women’s Relief. New places of service were added in Pforzheim and Davos. In addition, the rights of the nurses increased after the war; they were, for example, given greater participation in the administrative council. In the following years, pension conditions for nurses improved, holidays were introduced, the age for admission was lowered to 19 years, and training extended to two years. In 1933 the number of nurses (47) and the number of students (13) reached the highest levels in the history of the association.

From 1933 to forced dissolution

When the National Socialists came into power in 1933 there were immediate consequences for work of the members of the association. The number of patients in the Jewish institutions rose because they were less often admitted to other houses. Nurse training with state recognition continued in 1933, but in 1938 the title conferred was “Jewish nurse.” In 1939 the city began the expropriation of properties belonging to the Jewish community. In 1949 the association was forcibly disbanded. The Mother House was seized by the Gestapo at the end of 1940 and the University Hospital was given as alternative quarters. In the housing of the association members the number of nurses and students moving in and out increased markedly. Close study of the house records in the time from 1933 to 1942 show that the whereabouts of many of the residents is unclear; the fate of “99 (persons) can be clearly be attributed to the persecution and destruction of the National Socialists (Steppe, 1997). Many of them were killed in the extermination camps.

In October 1943 the nurse’s residence located at Bornheimer Landwehr 85 was completely destroyed by bombing; it had by that time been fully cleansed of Jews and was completely “Aryan” Many children and 14 nurses working at the University Hospital lost their lives.

Edgar Bönisch, 2009

(Translated by Yvonne Ford)

Reference

Steppe, Hilde 1997: “ … den Kranken zum Troste und dem Judenthum zur Ehre …“. Zur Geschichte der jüdischen Krankenpflege in Deutschland. Frankfurt/M.