Introduction

In the middle ages an infirmary mainly acted as a disease hospital (e.g. for lepers), where the “inmates” were separated from the healthy population and “kept” like prisoners, sometimes for life. In the course of industrialization the infirmary changed into an asylum for needy people with physical disabilities, chronic diseases and disabilities. Due to familiar and village networks being torn apart by migration to the cities, as well as the increasing specialization of hospitals on curable patients, no one could take care of them and they vegetated. Also old people found shelter in asylusm. Before the “first pure nursing homes and infirmaries” were established in the 19th century, they “had been accommodated in alms- and workhouses, where also ‚persons with bad reputation‘, ‚morons‘, ‚incorrigible alcoholics‘, ‚work-shy individuals‘ and offenders lived” (Graber-Dünow 2013: 245). Frail people had to work for their living, wear prison clothes and fear physical abuses. Here it was necessary to remedy the situation: Professional “Homes for the Incurable” (Stolberg 2011: 71) were the predecessors of today´s modern retirement and nursing homes and inpatient hospices. In addition to Gumpertz´ infirmary these include in Frankfurt am Main the municipal almshouse and infirmary called “Sandhöfer Allee” (later “Sandhof Hospital”), the Schmidborn-Rücker´s infirmary, the Karl and Emilie Jaeger´s children´s infirmary run by the Deaconess Association and since 1922 also the Jewish founded Rödelheim Hospital (cp. file inventory of ISG Ffm).

The accelerated industrialization in the Wilhelmine era posed new challenges also for the Jewish communities. Thus, the need for care increased in Frankfurt´s East End, where low-income Jewish people lived, and where, since the 1880s, persons displaced due to anti-Semitism had been arriving from Eastern Europe. The Jewish religious society (conservative secession community, which had left the bigger liberal Frankfurt am Main Jewish community) was worried about the appropriate ritual care of dependent Jewish people. The result of these considerations was an independent in-patient facility for frail, terminally ill and bedridden needy people of Jewish faith: Gumpertz´ infirmary, however, was,according to the provisions of Bikkur Cholim (Jewish obligation to patient visits or nursing),also open for non-Jewish people. After humble beginnings the infirmary united professional nursing, care of the elderly and severely disabled as well as poor relief under one roof. Soon it developed into an important protagonist of the local Jewish welfare system. Very impressive are the number and volume of endowments and donations by members of Frankfurt´s two Jewish communities: for free beds, equipment for medical treatment and care, books and other cultural activities, the organization of the religious festivities, the construction and maintenance of the in-house synagogue, which was officially opened in 1911 (cp. Gumpertz´ infirmary 1909 and 1913 et seqq.). The great importance of the synagogue for the residents of the facility is reflected, among other things, in the fact that the infirmary employed with Salomon Wolpert its own in-house rabbi.

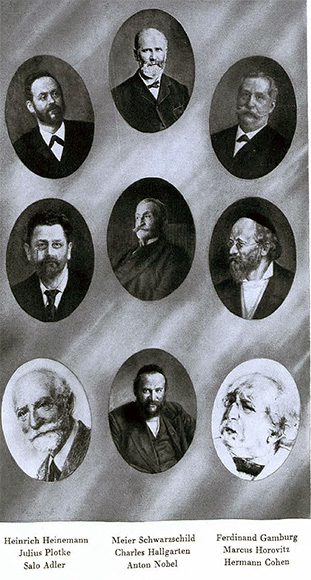

Gut, Elias 1928: History of the Frankfurt Lodge (1888-1928). Frankfurt a.M. 1928 (between p. 70 u. 71)

The beginnings

In 1888 the Frankfurt Jewish foundress Betty Gumpertz initiated Gumpertz´ Infirmary, bearing the name ofthe association which had been named after her. It was established in order to “provide accommodation and care for destitute, chronically ill, ailing people of both sexes” and to grant them competent “medical care” instead of simply custody (Gump Statute 1895: 3). According to the statutes the intention was “not to consider the religious denomination with regard to the services offered by the association. Since this aim, however, could not be achieved due to the limited resources of the association, only sick people of Jewish faith shall be considered. However, if these are not present, non-Jewish may also be accommodated by decision of the board” (ibid.: 4). The applicants shall have a “good reputation” – a certificate of “moral conduct” had to be submitted to the examining board – and should have lived in Frankfurt for at least two years. Accommodation and care were usually free of charge. In accordance with the statute there was “a room for the performance of the prayers according to strict Jewish rite” (ibid.: 5), where the foundress Betty Gumpertz herself and her deceased family members were commemorated.

In 1895 the board of the Gumpertz´ Infirmary association consisted of the well-known social reformer and chairman Charles L. Hallgarten as well as Michael Moses Mainz (vice chairman), Julius Goldschmidt (secretary to the board, later president), Joseph Holzmann (counter secretary), director Hermann Rais (treasurer), Hermann Schott (economist), Raphael Ettlinger (vice secretary to the board and vice economist), the banker Otto Höchberg (assessor) and the solicitor Julius Plotke (assessor). Probably because women were not allowed to lead any associations or clubs in the German Empire until 1908 in accordance with the Prussian law governing organizational affairs, Betty Gumpertz was involved in her foundation as an honorary member and “lady of honor” (ibid.: 8); furthermore, she was authorized to nominate a second lady of honor. On 11th May 1895 Gumpertz´ infirmary obtained the status as a legal entity under public law.

© Institute for the History of Frankfurt am Main

The locations

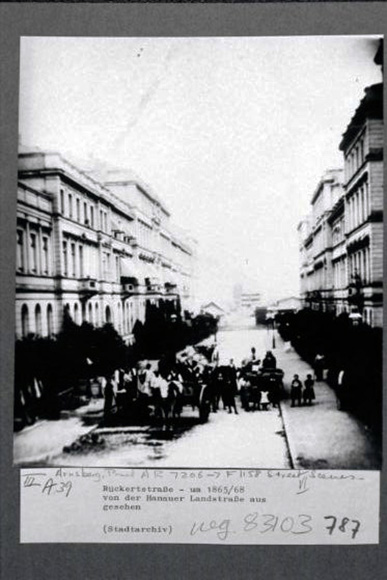

In 1888 Gumpertz´ infirmary started as a small inpatient facility on Rückertstrasse (Arnsberg 1983 vol. 1: 764 and vol. 2: 120; Cohn-Neßler 1920: 174; Schiebler 1994: 135, 282). The hosting capacities were quickly exhausted. Betty Gumpertz´ large donation of RM 60,000 made the purchase of the property at 75 Ostendstrasse possible, where a building with initially 20 beds was opened in 1892 (ISG Ffm: welfare office Sign. 877). The board of the association determined the 10th October 1892 as the official founding date. In September 1893 another generous foundress, Träutchen Höchberg, provided the infirmary, which was increasingly in demand, with RM 50,000 (cp. Schiebler 1994: 135). Nevertheless, the premises came up against limiting factors again due to the continuing demands for care outside the home. It was rescued by the annexation of the (dependent) Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Foundation, established in 1905, to the association Gumpertz´ Infirmary: Thanks to the large donation of one million Marks initiated by Mathilde von Rothschild a new building with at least 60 beds (cp. ibid.) was built at 62-64 Röderbergweg, which was also called “Rothschild´s Infirmary”. “[…] due to this magnificent building located in the middle of the old park, the Jewish nursing home and infirmary was, like its long-term administrator Hermann Seckbach emphasized, “enabled to treat and care for its patients in case of necessary operations or the like on its own, because the foundation building had theatres, x-ray facilities, laboratory and the most diverse electrical and other baths available” (Seckbach 1917). In addition to the newly constructed “front house” the property 62-64 Röderbergweg comprised a smaller old “rear building” (building of the association “Gumpertz´ Infirmary), which caused the senior doctor Dr. Alfred Günzburg a lot of worry: “According to the express wish of the foundress [Mathilde von Rothschild for her daughter Minka who passed away in 1903, B.S.] only women are admitted to the new foundation, while men are cared for in the old house, an old villa converted for hospital purposes, in a makeshift way, where bathrooms, toilets and sculleries are missing. There is no sitting room! A lift for persons is urgently needed in order to take slow-moving persons into the garden. Now the board is approached with the urgent task of rebuilding the men´s house in such a way that it meets the most important requirements of modern health care” (Gumpertz´ Infirmary 1909, page 7 et seqq.).

The urgently needed rebuilding measures were carried out, and also the big “front house” was further modernized. The subdivision into a “men´s house” (rear building) and a “women´s house” (front house) still existed during World War I.

In addition to the nursing care in “Rothschild´s Hospital” and the pediatric nursing in Rothschild´s Children´s Hospital, Gumpertz´ infirmary was the third cornerstone of care provision on Röderbergweg (also see Eckhardt 2006; Krohn 2000). All three facilities were close to the conservative-Jewish religious society and in corresponding contact.

Military hospital during World War I

Right after the beginning of the First World War Gumpertz´ infirmary was involved in Frankfurt´s nursing in 1914. Run as military hospital 33, it set up an intensive care ward for officers and soldiers with up to 40 beds. Soldiers of all denominations found accommodation there so that, in addition to Jewish festivities, Christmas was also celebrated. “It was occupied from its mobilization until 12th December 1918, accommodated 671 soldiers, including 434 wounded men. Furthermore, 154 military persons were treated there as outpatients” (Jewish nurse association Ffm 1920, page 36). The administrator Hermann Seckbach also took the military hospital under his proven wing. Under the direction of his future wife, matron Rahel Spiero, some of her colleagues of the Association for Jewish Nurses of Frankfurt am Main, whose names have not been passed on yet, worked there. Also the residents of the infirmary soon became active: Some male patients solemnized a “Jahrzeitstiftung ” for dead soldiers, “…a light is lit in the synagogue of our facility daily during the year of mourning and on the day of death fburns continuously and a Kaddish prayer alternately performed by the patients” (accountability report 1914 and 1915 (1916, page 7), cp. Gumpertz´ infirmary 1913 et seqq.).

Report of the association of the charity „Gumpertz’sches Siechenhaus“ and the Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Charity 1913 ff

In addition to the military hospital the regular care operation had to be continued: “On 1st January 1916 there were 35 women and 22 men in our facilities. In three years 24 women and 20 men newly joined us. 28 women and 25 men died or were dismissed so that on 1st January 1919 there were 31 women and 17 men in our facilities” (accountability report 1916, 1917 and 1918 (1919, page 4), cp. Gumpertz´ infirmary 1913 et seqq.). On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Gumpertz´ infirmary the administrator and author Hermann Seckbach, who also defended his protégés in a journalistic way, emphasized in the newspaper “Frankfurt´s news” in 1917: “[…] for many years we have regarded it as our most important task not to let people suffering from [sic!] long-term illnesses to simply drift-off. Thus, we find a number of cases which could be given back to life and their families or who work within our facility as employees” (Seckbach 1917).

After the end of war Mathilde von Rothschild and the family of her deceased daughter Minka – her husband Max von Goldschmidt-Rothschild and their children Albert, Rudolf, Lili, Lucy and Erich – did everything to take Gumpertz´ infirmary through the difficult inflation years.

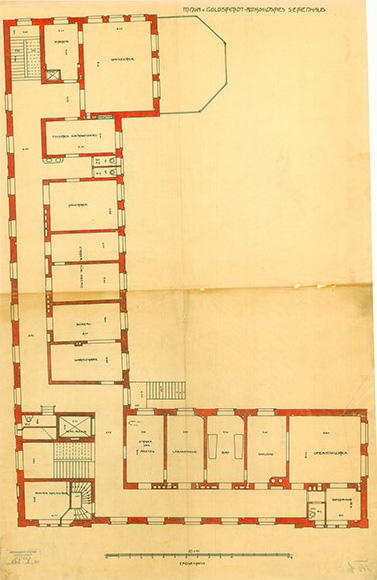

The 1920s

In Fanny Cohn-Nessler´s newspaper report “The infirmary of Frankfurt” from 1920, which is still worth reading today, it says with praise: “The Minka-von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Foundation, a stately elongated building of red sandstone and bricks, near the East Railway Station (Hanau Railway) and a beautiful park, faces Röderbergweg. The infirmary, coming from a legacy of Mrs Gumpertz […], now has received its own big house in the garden of the above-mentioned foundation. Both facilities enjoy a particularly good reputation among the welfare facilities of the old empire city. […] it is a conventional figure of speech in Frankfurt: best food and best agreement among the residents can be found in these two homes that are one; because both facilities are equipped for chronically ill and frail individuals” (Cohn-Nessler 1920: 174 [pointed out in the original]). The author provides also insights into the internal architecture and furnishings: “When entering the foundation you come into the posh-looking vestibule. Marble cladding, alternating with yellow polished wooden surfaces, mirrors on the walls, wide wooden staircases with carved railings” (ibid.). On the ground floor of the front house of the Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Foundation described above could be found among others, the doctors´ room, the room of the house nurse, examination rooms and theatres, the x-ray room as well as the dining room used for festivities. Visitor Fanny Cohn-Nessler was particularly impressed by a room being filled by a large Shabbat furnace (furnace for keeping food warm for the Shabbat): “The house is run in a strict ritual manner. The Shabbat furnace keeps food and drinks warm at a consistently hot (high) temperature during the whole Saturday. For a capacity of about hundred people – including the administration, care and service staff. A tunnel train connects both properties [front and rear building, B.S.]. The food train (lowry wagon) runs in both directions and carries the food including the necessary dishes, cutlery [sic] etc. to the different elevators, which are on all floors. The big kitchen, provided with all equipment of modern times, is located in the basement; also a pesah-kitchen. […] The laundry is on the second floor and equipped with steam operation following the example of large laundries in Berlin and other cities” (ibid.). The rooms of the men´s and women´s division were decorated in white. A large conservation room promoted the communication among the still mobile residents.

Due to the specialization of Gumpertz´ infirmary on long-term care it referred to itself temporarily with the name affix of “Jewish Nursing Home and Infirmary”. In order to remedy its financial difficulties – like almost all social and care institutions, the infirmary fought economic problems in the 1920s – the board strove to upgrade the infirmary to the status of a hospital. However, it continued to be classified as an infirmary and a nursing home by order of the authorities, since short-term care and outpatient clinic were missing. Probably that was why it cut down the operation of its hospital in favor of the elderly care in 1922. In 1929 Gumpertz´ infirmary had to rent its main building (front house) with 90 beds for initially 20 years to the City of Frankfurt am Main, whose aim was to expand the municipal medical care, but reserved in the lease contract the option to buy the complete property. The infirmary itself retreated into its second building (rear building), a villa with 30 beds. The City of Frankfurt agreed to pay the annual rent for the front house and took on maintenance and renovation work. It also planned building extensions with integrated apartments for the nurses. On 27th July 1931 the front house was assigned to the City Health Office as health institution in accordance with the decision of the Magistrate and run as a so-called “mixed” business – with a bigger department for chronically ill patients and a smaller infirmary department – by the chamber office of the Hospital of the Holy Spirit. As a result of the severely fluctuating occupancy of Frankfurt´s hospital beds, the concept of the Municipal Hospital East” and also of a “Municipal Infirmary” was discarded again; instead, spare beds should be made available in the “front house” e.g. for influenza epidemics (ISG Ffm: welfare office Sign. 877; magistrate records Sign. 8.957).

The NS-era

After the seizure of power by the national socialists the City of Frankfurt intended to sublease Gumpertz´ front house to the military police department of the major detachment IV of the Stormtroopers (“SA”) of the NSDAP as their military police station. Since this initially could not be realized, the city suddenly terminated the lease contract in May 1933. The Gumpertz´ Foundation, represented by its chairman Dr. Richard Merzbach, instituted proceedings against the sudden termination of the contract, which was a sign that not just the loss of workplaces for the (now -predominantly Christian) nursing staff was on its way, but also the financial ruin for the whole institution. The SA-military-police-department asserted its interest in a take-over in a rude manner: If the city does not exert appropriate pressure on the Jewish landlord, the military police station would possibly move in without having permission. The department even threatened to report the infirmary because of sabotage (ISG Ffm: magistrate records Sign. 8.957: Letter of the Lord Mayor Krebs dated 02/10/1933). Finally, the infirmary had to leave the front house to the city at reduced rent and without the condition to use the building solely for hospital purposes. In accordance with a magistrate decision of 16th October 1933 the SA-military-police-department moved into the front house on 4th November 1933, where 65 persons lived in April 1934. Thus, Gumpertz´ infirmary had a National Socialist neighbor on its own property. On top of everything it was still in disputes over the lease with the city which had in the meantime stopped its payments. Official sublease for the SA-military-police-corps was the “Prussian Treasury” from 1934 until 1936 (with a renewal option until 1944) that was to share the renovation and maintenance costs in equal parts with the City of Frankfurt. However, there was an argument concerning this topic with the city, especially because the military police delayed their rental payments. After the move-out of the military police the 1st unit of hundred policemen of Frankfurt´s uniformed police was initially accommodated in the front house in 1936/37 until being transferred into “Gutleut” barracks. They were temporarily followed by “Hitler-vacationers-comradeships” (in 1937), who consisted of older national socialists “of outstanding merit” like political leaders, storm troopers and members of the shield squadron.

Due to increased demand the front house was to be used as a nursing home and infirmary again in the fall of 1937 and purchased as “inexpensively” as possible by the Gumpertz Foundation. In addition, the Office for “Social Self-Responsibility” of the Nazi German Labour Front intended to establish a research institute for slim diseases in order to counteract reduced efficiency of the Aryan labor force, whether due to overload in the workplace or unhealthy lifestyle, by targeted preventive and optimization measures. In 1937 kitchen, main pantry for food distribution, dining and dressing rooms for the staff, rooms for the storage of hospital clothes and dirty laundry, heating and domestic hot water production plants were located in the basement, on the first floor there were a hospital ward with 13 beds, a room for the medical director of the aforementioned research institute together with a secretarial pool, a room for the cardiac event recorder, a chemical examination room, two physical examination rooms, the diagnostic radiology department with darkroom and the porter´s room, on the second and third floor a hospital ward with 38 beds and adjoining rooms each. In the attic you found the living areas for a doctor, a senior nurse, 15 nurses and 14 domestic servants. In 1938 the city announced its intention to purchase the entire property 62-64 Röderbergweg extending to Danziger Platz and Henschelstrasse, which was certainly rejected by the Gumpertz´ Foundation. However, in April 1938 the foundation had to agree to the sale of its front house which was then called “Röderbergweg Nursing Home and Infirmary”, in short Röderbergweg Home. The “Hospital of the Holy Spirit” took over the management and had extensive reconstruction and renovation work done. After its official opening on 21st November the Röderbergweg Home was occupied with 26 (non-Jewish) chronically ill and ailing patients in agreement with the welfare office (ISG Ffm: magistrate records Sign. 8.958).

The (dependent) Gumpertz´ Infirmary Foundation and Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild Foundation were forcibly incorporated into the “Empire´s Association of German Jews” (ISG: foundation department: Sign. 146) on 28th September 1940. On 7th April 1941 the NS-authorities forced the nursing staff and the 46 patients out of the rear building (since 1932 under the address: Danziger Platz 15) transferring to the Hospital of the Jewish Community (at 36 Gagernstrasse). Their biographic data and further destiny are still unexplored: Were they deported to Theresienstadt ghetto like Siegmund Keller and the matron of Gumpertz´ infirmary, Rahel Seckbach? Did some fall prey to not only the Shoah, but also the eugenic Nazi mass murder of disabled people (T4) (see Lilienthal 2009)? In accordance with the “Hausstandsbüchern” [records kept by the local police stations that listed Frankfurt´s residents sorted by street and house number] for 36 Gagernstrasse (ISG Ffm: Part 2, Sign. 687) many displaced patients from the house at 15 Danziger Platz died still in hospital, which was not even equipped for the care of chronically ill patients. With regard to the staff, the “deportees database” of the Börneplatz memorial (Jewish museum of Frankfurt am Main) registers under the address 15 Danziger Platz, in addition to the longstanding domestic employee Rachel Kaplan, the nurse intern Edith Appel (nurse interns), Leopold Lion (porter) and Zilla Reiss (cook, teaching nurse); the “Hausstandsbücher” (ISG Ffm: Part 2, Sign. 687) listed Cornelie (Cornelia) Butwies (commercial clerk, nurse, page 16, 18) as well as Klara Strauss (cook, page 341). In the beginning of 1942 the Empire´s Association of German Jews “sold” the remaining property at 15 Danziger Platz, where the commander´s office of Frankfurt am Main immediately set up the front control center and a teaching kitchen of the Air Force, under Nazi conditions. In 1944 allied air raids destroyed the property of the “Arianized” Gumpertz´ / Rothschild´s infirmary on Röderbergweg. The (non-Jewish) residents had been transferred already before the bombings: the chronically ill patients to Lange Strasse (Hospital of the Holy Spirit) and the sick patients to the Forest Hospital of Köppern near Friedrichsdorf (Taunus). Did they get caught up in the wheels of the eugenic Nazi mass murder (cp. for Hesse among others Daub 1992; Hahn 2001; Leuchtweis-Gerlach 2001; Sandner 2003; also see Graber-Dünow 2013)?

© Institut für Stadtgeschichte, Frankfurt am Main, Sig. S7C1998_30.569

Since 1956 the nursing facility “August-Stunz-Zentrum” of the Workers´ Welfare has been located on the property, today 82 Röderbergweg. On July 25th, 2015, a memorial plaque of the Gumpertz Infirmary is placed on the entrance area of the “August-Stunz-Zentrum”.

I thank Simone Hofmann (B’nai B’rith Frankfurt Schönstädt Lodge, Frankfurt am Main), Felicitas Gürsching (“Library of the Old” of the Historical Museum of Frankfurt am Main), Hanna and Dieter Eckhardt (Historical workshop of the Workers‘ Welfare Frankfurt am Main), Annette Handrich, and Dr. Siegbert Wolf (both City Archive Frankfurt am Main) for important leads.

Birgit Seemann, 2013, updated 2018

(Translated by Yvonne Ford)

Unpublished sources

ISG Ffm: Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main:

Hausstandsbücher Gagernstraße 36: Sign. 686 (Teil 1); Sign. 687 (Teil 2).

Magistratsakten: Sign. 8.756: Fürsorgewesen: Siechenheime.

Magistratsakten: Sign. 8.957: Städtische Krankenanstalten: Ermietung des Gumpertzschen [sic] Siechenhauses zur Unterbringung von Kranken und Weiterverpachtung an die Feldjägerei (1930–1938).

Magistratsakten: Sign. T/ 3.028 (Tiefbau- und Hochbauamt, 1904, 1916).

Magistrat: Nachträge Sign. 19 u. Sign. 110.

Sammlung Ortsgeschichte / S3N: Sign. 5.150: Gumpertzsches [sic] Siechenhaus.

Stiftungsabteilung: Sign. 146: Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung (1939-1940).

Wohlfahrtsamt: Sign. 877 (1893–1928): Magistrat, Waisen- und Armen-Amt Frankfurt a.M.

Selected Literature

Andernacht, Dietrich/ Sterling, Eleonore (Bearb.) 1963: Dokumente zur Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden 1933-1945. Hg.: Kommission zur Erforschung der Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden. Frankfurt/M.

Anonym. 1909: [Rubrik ‚Vermischtes‘: Zeitungsnotiz Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus.] In: Der Israelit, Nr. 50, 16.12.1909. Online-Ausg. Univ.-Bibliothek Frankfurt/M.: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-151202.

Anonym. 1912: [Zeitungsnotiz: Wohlfahrtspflege.] In: Deutscher Reichsanzeiger (Berlin), Nr. 176, 25.07.1912. Online-Ausg. Univ.-Bibliothek Frankfurt/M.: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-151202.

Arnsberg, Paul 1983: Die Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden seit der Französischen Revolution. Darmstadt, 3 Bände.

Cohn-Neßler, Fanny 1920: Das Frankfurter Siechenhaus. Die Minka-von-Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung. In: Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums 1920, H. 16 (16.04.1920), S. 174-175 [Online-Ausg.: www.compactmemory.de].

Daub, Ute 1992: „Krankenhaus-Sonderanlage Aktion Brandt in Köppern im Taunus“ – Die letzte Phase der „Euthanasie“ in Frankfurt am Main. In: Psychologie und Gesellschaftskritik 16 (1992) 2, Online-Ausg. 2011: http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/26651.

Eckardt, Hanna 2006: Der Röderbergweg, einst beispielhafte Adresse jüdischer Sozialeinrichtungen. In: Zu Hause im Ostend. 50 Jahre August-Stunz-Zentrum. Festschrift zum 50-jährigen Jubiläum. Hg. von der Geschichtswerkstatt der AWO Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt a.M., S. 10-13.

Graber-Dünow, Michael 2013: Zur Geschichte der „Geschlossenen Altersfürsorge“ von 1919 bis 1945. In: Hilde Steppe (Hg.): Krankenpflege im Nationalsozialismus. 10., aktualis. u. erw. Aufl. Frankfurt/M., S. 245-255.

GumpSiechenhaus 1909: Sechzehnter Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ in Frankfurt a.M. für das Jahr 1908. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky.

GumpSiechenhaus 1913ff.: Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ und der „Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung“. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky, 1913ff. [Online-Ausg.: Univ.-Bibl. Frankfurt/M. 2011: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-306391].

GumpSiechenhaus 1936: Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus. [Bericht von der Generalversammlung des Vereins.] In: Der Israelit, 20.05.1936, Nr. 21, S. 14f. [Online-Ausg.: http://edocs.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/volltexte/2008/38052/original/Israelit_1936_21.pdf].

GumpStatut 1895: Revidirtes Statut für den Verein Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus zu Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.: Druck v. Benno Schmidt, Stiftstraße 22. [ISG Ffm: Sammlung S3/N 5.150].

Hahn, Susanne 2001: Köppern als Alten- und Siechenheim in der Trägerschaft zum Heiligen Geist in Frankfurt am Main seit 1934 und die „Aktion Brandt“. In: Vanja, Christina/ Siefert, Helmut (Hg.) 2001: „In waldig-ländlicher Umgebung“. Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern: Von der agrikolen Kolonie der Stadt Frankfurt zum Zentrum für Soziale Psychiatrie Hochtaunus. Kassel, S. 196-219.

Jüdischer Schwesternverein Ffm 1920: Verein für jüdische Krankenpflegerinnen zu Frankfurt a.M.: Rechenschaftsbericht 1913 bis 1919. Frankfurt/M.

Kallmorgen, Wilhelm 1936: Siebenhundert Jahre Heilkunde in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.

Kingreen, Monica (Hg.) 1999: „Nach der Kristallnacht“. Jüdisches Leben und antijüdische Politik in Frankfurt am Main 1938 – 1945 Frankfurt/M., New York.

Krohn, Helga 2000: „Auf einem der luftigsten und freundlichsten Punkte der Stadt, auf dem Röderberge, sind die jüdischen Spitäler“. In: dies. [u.a.]: Ostend. Blick in ein jüdisches Viertel. [Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Jüdischen Museum Frankfurt/M.]. Mit Beitr. v. Helga Krohn […] u. e. Einl. v. Georg Heuberger. Erinnerungen von Wilhelm Herzfeld [u.a.]. Frankfurt/M., S. 128-143.

Leuchtweis-Gerlach, Brigitte 2001: Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern (1901 – 1945). Die Geschichte einer psychiatrischen Klinik. Frankfurt/M.

Lilienthal, Georg 2009: Jüdische Patienten als Opfer der NS-„Euthanasie“-Verbrechen. In: Medaon – Magazin für jüdisches Leben in Forschung und Bildung, Ausgabe 5, 09.11.2009: www.medaon.de.

Otto, Arnim 1998: Juden im Frankfurter Osten 1796 bis 1945. 3., bearb. u. veränd. Aufl. Offenbach/M., S. 220f.

Sandner, Peter 2003: Verwaltung des Krankenmordes. Der Bezirksverband Nassau im Nationalsozialismus. Gießen.

Schiebler, Gerhard 1994: Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger. In: Lustiger, Arno (Hg.) 1994: Jüdische Stiftungen in Frankfurt am Main. Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger dargest. v. Gerhard Schiebler. Mit Beitr. v. Hans Achinger [u.a.]. Hg. i.A. der M.-J.-Kirchheim’schen Stiftung in Frankfurt am Main. 2. unveränd. Aufl. Sigmaringen 1994, S. 11-288.

Seckbach, Hermann 1917: Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Siechenhaus. Von Verwalter H. Seckbach. In: Frankfurter Nachrichten, 20.09.1917.

Seemann, Birgit 2014: „Glück im Hause des Leids“. Jüdische Pflegegeschichte am Beispiel des Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses (1888-1941) in Frankfurt/Main. In: Geschichte der Pflege. Das Journal für historische Forschung der Pflege- und Gesundheitsberufe 3 (2014) 2, S. 38-50

Seemann, Birgit 2017: Judentum und Pflege: Zur Sozialgeschichte des orthodox-jüdischen Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses in Frankfurt am Main (1888–1941). In: Nolte, Karin/ Vanja, Christina/ Bruns, Florian/ Dross, Fritz (Hg.): Geschichte der Pflege im Krankenhaus. Historia Hospitalium. Jahrbuch der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Krankenhausgeschichte, Band 30. Berlin, S. 13-40

Seide, Adam 1987: Rebecca oder ein Haus für Jungfrauen jüdischen Glaubens besserer Stände in Frankfurt am Main. Roman. Frankfurt a.M.

Steppe, Hilde 1997: „… den Kranken zum Troste und dem Judenthum zur Ehre …“. Zur Geschichte der jüdischen Krankenpflege in Deutschland. Frankfurt/M.

Stolberg, Michael 2011: Fürsorgliche Ausgrenzung. Die Geschichte der Unheilbarenhäuser (1500–1900). In: Stollberg, Gunnar u.a. (Hg.): Krankenhausgeschichte heute. Was heißt und zu welchem Ende studiert man Hospital- und Krankenhausgeschichte? Berlin, Münster = Historia hospitalium; Bd. 27, S. 71-78.

Zenker, Dinah 2013: Spiritualität in der Pflege. Ein Ansatz und ein Plädoyer aus der Perspektive der jüdischen Orthodoxie. In: Dachs, Gisela (Hg.): Alter. Jüdischer Almanach der Leo Baeck Institute. Hg. im Auftr. des Leo Baeck Instituts Jerusalem. 2. Aufl. Berlin, S. 127-134.

Selected internet sources (last visited 24.10.2017)

Alemannia Judaica: Alemannia Judaica – Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Erforschung der Geschichte der Juden im süddeutschen und angrenzenden Raum: www.alemannia-judaica.de.

ISG Ffm: Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main (mit Datenbank): www.stadtgeschichte-ffm.de sowie http://www.ffmhist.de/

JM Ffm: Jüdisches Museum und Museum Judengasse Frankfurt am Main (mit der internen biographischen Datenbank der Gedenkstätte Neuer Börneplatz): www.juedischesmuseum.de.

MJ Ffm: Museum Judengasse Frankfurt am Main (Infobank): http://www.museumjudengasse.de/de/home/

Magistratsakten: Sign. T/ 3.028 (Tiefbau- und Hochbauamt, 1904, 1916).

Magistrat: Nachträge Sign. 19 u. Sign. 110.

Sammlung Ortsgeschichte / S3N: Sign. 5.150: Gumpertzsches [sic] Siechenhaus.

Stiftungsabteilung: Sign. 146: Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung (1939-1940).

Wohlfahrtsamt: Sign. 877 (1893–1928): Magistrat, Waisen- und Armen-Amt Frankfurt a.M.

Selected Literature

Andernacht, Dietrich/ Sterling, Eleonore (Bearb.) 1963: Dokumente zur Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden 1933-1945. Hg.: Kommission zur Erforschung der Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden. Frankfurt/M.

Anonym. 1909: [Rubrik ‚Vermischtes‘: Zeitungsnotiz Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus.] In: Der Israelit, Nr. 50, 16.12.1909. Online-Ausg. Univ.-Bibliothek Frankfurt/M.: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-151202.

Anonym. 1912: [Zeitungsnotiz: Wohlfahrtspflege.] In: Deutscher Reichsanzeiger (Berlin), Nr. 176, 25.07.1912. Online-Ausg. Univ.-Bibliothek Frankfurt/M.: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-151202.

Arnsberg, Paul 1983: Die Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden seit der Französischen Revolution. Darmstadt, 3 Bände.

Cohn-Neßler, Fanny 1920: Das Frankfurter Siechenhaus. Die Minka-von-Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung. In: Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums 1920, H. 16 (16.04.1920), S. 174-175 [Online-Ausg.: www.compactmemory.de].

Daub, Ute 1992: „Krankenhaus-Sonderanlage Aktion Brandt in Köppern im Taunus“ – Die letzte Phase der „Euthanasie“ in Frankfurt am Main. In: Psychologie und Gesellschaftskritik 16 (1992) 2, Online-Ausg. 2011: http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/26651.

Eckardt, Hanna 2006: Der Röderbergweg, einst beispielhafte Adresse jüdischer Sozialeinrichtungen. In: Zu Hause im Ostend. 50 Jahre August-Stunz-Zentrum. Festschrift zum 50-jährigen Jubiläum. Hg. von der Geschichtswerkstatt der AWO Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt a.M., S. 10-13.

Graber-Dünow, Michael 2013: Zur Geschichte der „Geschlossenen Altersfürsorge“ von 1919 bis 1945. In: Hilde Steppe (Hg.): Krankenpflege im Nationalsozialismus. 10., aktualis. u. erw. Aufl. Frankfurt/M., S. 245-255.

GumpSiechenhaus 1909: Sechzehnter Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ in Frankfurt a.M. für das Jahr 1908. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky.

GumpSiechenhaus 1913ff.: Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ und der „Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung“. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky, 1913ff. [Online-Ausg.: Univ.-Bibl. Frankfurt/M. 2011: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-306391].

GumpSiechenhaus 1936: Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus. [Bericht von der Generalversammlung des Vereins.] In: Der Israelit, 20.05.1936, Nr. 21, S. 14f. [Online-Ausg.: http://edocs.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/volltexte/2008/38052/original/Israelit_1936_21.pdf].

GumpStatut 1895: Revidirtes Statut für den Verein Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus zu Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.: Druck v. Benno Schmidt, Stiftstraße 22. [ISG Ffm: Sammlung S3/N 5.150].

Hahn, Susanne 2001: Köppern als Alten- und Siechenheim in der Trägerschaft zum Heiligen Geist in Frankfurt am Main seit 1934 und die „Aktion Brandt“. In: Vanja, Christina/ Siefert, Helmut (Hg.) 2001: „In waldig-ländlicher Umgebung“. Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern: Von der agrikolen Kolonie der Stadt Frankfurt zum Zentrum für Soziale Psychiatrie Hochtaunus. Kassel, S. 196-219.

Jüdischer Schwesternverein Ffm 1920: Verein für jüdische Krankenpflegerinnen zu Frankfurt a.M.: Rechenschaftsbericht 1913 bis 1919. Frankfurt/M.

Kallmorgen, Wilhelm 1936: Siebenhundert Jahre Heilkunde in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.

Kingreen, Monica (Hg.) 1999: „Nach der Kristallnacht“. Jüdisches Leben und antijüdische Politik in Frankfurt am Main 1938 – 1945 Frankfurt/M., New York.

Krohn, Helga 2000: „Auf einem der luftigsten und freundlichsten Punkte der Stadt, auf dem Röderberge, sind die jüdischen Spitäler“. In: dies. [u.a.]: Ostend. Blick in ein jüdisches Viertel. [Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Jüdischen Museum Frankfurt/M.]. Mit Beitr. v. Helga Krohn […] u. e. Einl. v. Georg Heuberger. Erinnerungen von Wilhelm Herzfeld [u.a.]. Frankfurt/M., S. 128-143.

Leuchtweis-Gerlach, Brigitte 2001: Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern (1901 – 1945). Die Geschichte einer psychiatrischen Klinik. Frankfurt/M.

Lilienthal, Georg 2009: Jüdische Patienten als Opfer der NS-„Euthanasie“-Verbrechen. In: Medaon – Magazin für jüdisches Leben in Forschung und Bildung, Ausgabe 5, 09.11.2009: www.medaon.de.

Otto, Arnim 1998: Juden im Frankfurter Osten 1796 bis 1945. 3., bearb. u. veränd. Aufl. Offenbach/M., S. 220f.

Sandner, Peter 2003: Verwaltung des Krankenmordes. Der Bezirksverband Nassau im Nationalsozialismus. Gießen.

Schiebler, Gerhard 1994: Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger. In: Lustiger, Arno (Hg.) 1994: Jüdische Stiftungen in Frankfurt am Main. Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger dargest. v. Gerhard Schiebler. Mit Beitr. v. Hans Achinger [u.a.]. Hg. i.A. der M.-J.-Kirchheim’schen Stiftung in Frankfurt am Main. 2. unveränd. Aufl. Sigmaringen 1994, S. 11-288.

Seckbach, Hermann 1917: Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Siechenhaus. Von Verwalter H. Seckbach. In: Frankfurter Nachrichten, 20.09.1917.

Seemann, Birgit 2014: „Glück im Hause des Leids“. Jüdische Pflegegeschichte am Beispiel des Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses (1888-1941) in Frankfurt/Main. In: Geschichte der Pflege. Das Journal für historische Forschung der Pflege- und Gesundheitsberufe 3 (2014) 2, S. 38-50

Seemann, Birgit 2017: Judentum und Pflege: Zur Sozialgeschichte des orthodox-jüdischen Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses in Frankfurt am Main (1888–1941). In: Nolte, Karin/ Vanja, Christina/ Bruns, Florian/ Dross, Fritz (Hg.): Geschichte der Pflege im Krankenhaus. Historia Hospitalium. Jahrbuch der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Krankenhausgeschichte, Band 30. Berlin, S. 13-40

Seide, Adam 1987: Rebecca oder ein Haus für Jungfrauen jüdischen Glaubens besserer Stände in Frankfurt am Main. Roman. Frankfurt a.M.

Steppe, Hilde 1997: „… den Kranken zum Troste und dem Judenthum zur Ehre …“. Zur Geschichte der jüdischen Krankenpflege in Deutschland. Frankfurt/M.

Stolberg, Michael 2011: Fürsorgliche Ausgrenzung. Die Geschichte der Unheilbarenhäuser (1500–1900). In: Stollberg, Gunnar u.a. (Hg.): Krankenhausgeschichte heute. Was heißt und zu welchem Ende studiert man Hospital- und Krankenhausgeschichte? Berlin, Münster = Historia hospitalium; Bd. 27, S. 71-78.

Zenker, Dinah 2013: Spiritualität in der Pflege. Ein Ansatz und ein Plädoyer aus der Perspektive der jüdischen Orthodoxie. In: Dachs, Gisela (Hg.): Alter. Jüdischer Almanach der Leo Baeck Institute. Hg. im Auftr. des Leo Baeck Instituts Jerusalem. 2. Aufl. Berlin, S. 127-134.

Selected internet sources (last visited 24.10.2017)

Alemannia Judaica: Alemannia Judaica – Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Erforschung der Geschichte der Juden im süddeutschen und angrenzenden Raum: www.alemannia-judaica.de.

ISG Ffm: Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main (mit Datenbank): www.stadtgeschichte-ffm.de sowie http://www.ffmhist.de/

JM Ffm: Jüdisches Museum und Museum Judengasse Frankfurt am Main (mit der internen biographischen Datenbank der Gedenkstätte Neuer Börneplatz): www.juedischesmuseum.de.

MJ Ffm: Museum Judengasse Frankfurt am Main (Infobank): http://www.museumjudengasse.de/de/home/

Stiftungsabteilung: Sign. 146: Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung (1939-1940).

Wohlfahrtsamt: Sign. 877 (1893–1928): Magistrat, Waisen- und Armen-Amt Frankfurt a.M.

Selected Literature

Andernacht, Dietrich/ Sterling, Eleonore (Bearb.) 1963: Dokumente zur Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden 1933-1945. Hg.: Kommission zur Erforschung der Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden. Frankfurt/M.

Anonym. 1909: [Rubrik ‚Vermischtes‘: Zeitungsnotiz Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus.] In: Der Israelit, Nr. 50, 16.12.1909. Online-Ausg. Univ.-Bibliothek Frankfurt/M.: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-151202.

Anonym. 1912: [Zeitungsnotiz: Wohlfahrtspflege.] In: Deutscher Reichsanzeiger (Berlin), Nr. 176, 25.07.1912. Online-Ausg. Univ.-Bibliothek Frankfurt/M.: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-151202.

Arnsberg, Paul 1983: Die Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden seit der Französischen Revolution. Darmstadt, 3 Bände.

Cohn-Neßler, Fanny 1920: Das Frankfurter Siechenhaus. Die Minka-von-Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung. In: Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums 1920, H. 16 (16.04.1920), S. 174-175 [Online-Ausg.: www.compactmemory.de].

Daub, Ute 1992: „Krankenhaus-Sonderanlage Aktion Brandt in Köppern im Taunus“ – Die letzte Phase der „Euthanasie“ in Frankfurt am Main. In: Psychologie und Gesellschaftskritik 16 (1992) 2, Online-Ausg. 2011: http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/26651.

Eckardt, Hanna 2006: Der Röderbergweg, einst beispielhafte Adresse jüdischer Sozialeinrichtungen. In: Zu Hause im Ostend. 50 Jahre August-Stunz-Zentrum. Festschrift zum 50-jährigen Jubiläum. Hg. von der Geschichtswerkstatt der AWO Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt a.M., S. 10-13.

Graber-Dünow, Michael 2013: Zur Geschichte der „Geschlossenen Altersfürsorge“ von 1919 bis 1945. In: Hilde Steppe (Hg.): Krankenpflege im Nationalsozialismus. 10., aktualis. u. erw. Aufl. Frankfurt/M., S. 245-255.

GumpSiechenhaus 1909: Sechzehnter Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ in Frankfurt a.M. für das Jahr 1908. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky.

GumpSiechenhaus 1913ff.: Rechenschaftsbericht des Vereins „Gumpertz`sches Siechenhaus“ und der „Minka von Goldschmidt-Rothschild-Stiftung“. Frankfurt/M.: Slobotzky, 1913ff. [Online-Ausg.: Univ.-Bibl. Frankfurt/M. 2011: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:1-306391].

GumpSiechenhaus 1936: Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus. [Bericht von der Generalversammlung des Vereins.] In: Der Israelit, 20.05.1936, Nr. 21, S. 14f. [Online-Ausg.: http://edocs.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/volltexte/2008/38052/original/Israelit_1936_21.pdf].

GumpStatut 1895: Revidirtes Statut für den Verein Gumpertz´sches Siechenhaus zu Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.: Druck v. Benno Schmidt, Stiftstraße 22. [ISG Ffm: Sammlung S3/N 5.150].

Hahn, Susanne 2001: Köppern als Alten- und Siechenheim in der Trägerschaft zum Heiligen Geist in Frankfurt am Main seit 1934 und die „Aktion Brandt“. In: Vanja, Christina/ Siefert, Helmut (Hg.) 2001: „In waldig-ländlicher Umgebung“. Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern: Von der agrikolen Kolonie der Stadt Frankfurt zum Zentrum für Soziale Psychiatrie Hochtaunus. Kassel, S. 196-219.

Jüdischer Schwesternverein Ffm 1920: Verein für jüdische Krankenpflegerinnen zu Frankfurt a.M.: Rechenschaftsbericht 1913 bis 1919. Frankfurt/M.

Kallmorgen, Wilhelm 1936: Siebenhundert Jahre Heilkunde in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt/M.

Kingreen, Monica (Hg.) 1999: „Nach der Kristallnacht“. Jüdisches Leben und antijüdische Politik in Frankfurt am Main 1938 – 1945 Frankfurt/M., New York.

Krohn, Helga 2000: „Auf einem der luftigsten und freundlichsten Punkte der Stadt, auf dem Röderberge, sind die jüdischen Spitäler“. In: dies. [u.a.]: Ostend. Blick in ein jüdisches Viertel. [Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Jüdischen Museum Frankfurt/M.]. Mit Beitr. v. Helga Krohn […] u. e. Einl. v. Georg Heuberger. Erinnerungen von Wilhelm Herzfeld [u.a.]. Frankfurt/M., S. 128-143.

Leuchtweis-Gerlach, Brigitte 2001: Das Waldkrankenhaus Köppern (1901 – 1945). Die Geschichte einer psychiatrischen Klinik. Frankfurt/M.

Lilienthal, Georg 2009: Jüdische Patienten als Opfer der NS-„Euthanasie“-Verbrechen. In: Medaon – Magazin für jüdisches Leben in Forschung und Bildung, Ausgabe 5, 09.11.2009: www.medaon.de.

Otto, Arnim 1998: Juden im Frankfurter Osten 1796 bis 1945. 3., bearb. u. veränd. Aufl. Offenbach/M., S. 220f.

Sandner, Peter 2003: Verwaltung des Krankenmordes. Der Bezirksverband Nassau im Nationalsozialismus. Gießen.

Schiebler, Gerhard 1994: Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger. In: Lustiger, Arno (Hg.) 1994: Jüdische Stiftungen in Frankfurt am Main. Stiftungen, Schenkungen, Organisationen und Vereine mit Kurzbiographien jüdischer Bürger dargest. v. Gerhard Schiebler. Mit Beitr. v. Hans Achinger [u.a.]. Hg. i.A. der M.-J.-Kirchheim’schen Stiftung in Frankfurt am Main. 2. unveränd. Aufl. Sigmaringen 1994, S. 11-288.

Seckbach, Hermann 1917: Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Siechenhaus. Von Verwalter H. Seckbach. In: Frankfurter Nachrichten, 20.09.1917.

Seemann, Birgit 2014: „Glück im Hause des Leids“. Jüdische Pflegegeschichte am Beispiel des Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses (1888-1941) in Frankfurt/Main. In: Geschichte der Pflege. Das Journal für historische Forschung der Pflege- und Gesundheitsberufe 3 (2014) 2, S. 38-50

Seemann, Birgit 2017: Judentum und Pflege: Zur Sozialgeschichte des orthodox-jüdischen Gumpertz’schen Siechenhauses in Frankfurt am Main (1888–1941). In: Nolte, Karin/ Vanja, Christina/ Bruns, Florian/ Dross, Fritz (Hg.): Geschichte der Pflege im Krankenhaus. Historia Hospitalium. Jahrbuch der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Krankenhausgeschichte, Band 30. Berlin, S. 13-40

Seide, Adam 1987: Rebecca oder ein Haus für Jungfrauen jüdischen Glaubens besserer Stände in Frankfurt am Main. Roman. Frankfurt a.M.